4X38X8

-

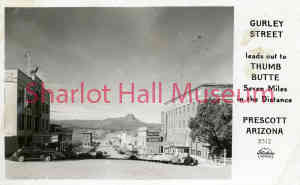

1090-0101-0000 Gurley Street Bridge in Winter Streets, Roads & Highways

-

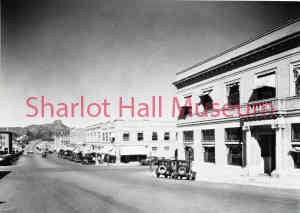

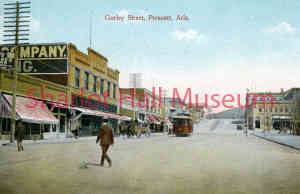

1090-0102-0004

Gurley Street Looking West

Streets, Roads & Highways -

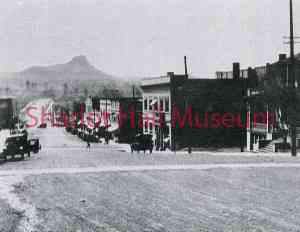

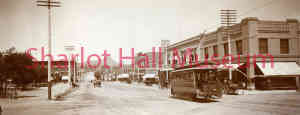

1090-0102-0005

Gurley Street Looking West

Streets, Roads & Highways -

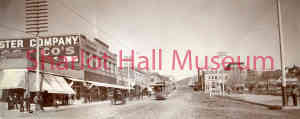

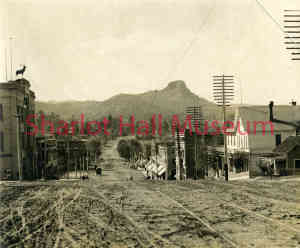

1090-0102-0006

Gurley Street Looking West

Streets, Roads & Highways -

1090-0103-0000 Gurley and Cortez Streets Streets, Roads & Highways

-

1090-0104-0000 Gurley Street Streets, Roads & Highways

-

1090-0105-0001 Gurley Street Streets, Roads & Highways

-

1090-0105-0002 Gurley Street Streets, Roads & Highways

-

1090-0106-0000 Gurley Street Streets, Roads & Highways

-

1090-0107-0001 Gurley Steet Streets, Roads & Highways

-

1090-0107-0002

Gurley Street

Streets, Roads & Highways -

1090-0107-0003 Gurley Street Streets, Roads & Highways