Havasupai Dwelling

Indians - Havasupai

4X38X8

-

1501-0416-0001

-

1501-0413-0000

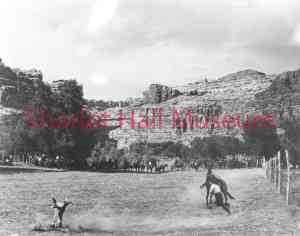

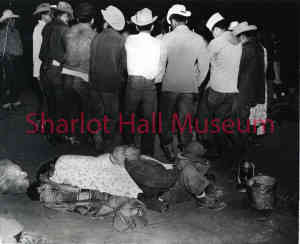

Havasupai Rodeo

Indians - Havasupai -

1501-0411-0000

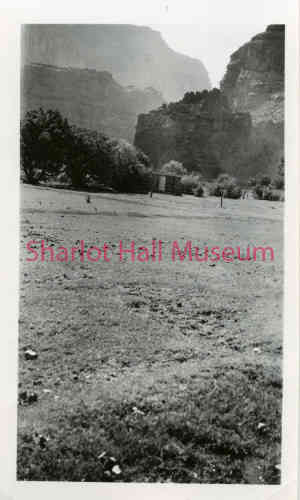

Havasupai Garden Plots

Indians - Havasupai -

1501-0410-0002

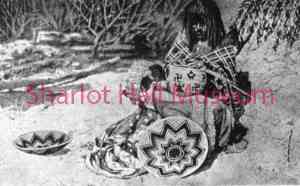

Havasupai Woman Weaving Baskets

Indians - Havasupai -

1501-0407-0000

Havasupai Men in Uniform

Indians - Havasupai -

1501-0406-0000

Havasupai Couple

Indians - Havasupai -

1501-0401-0000

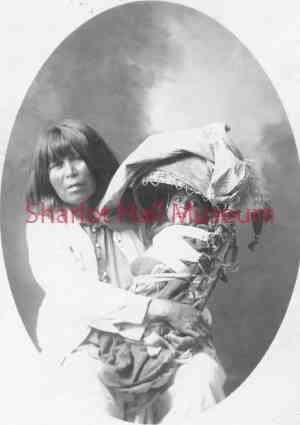

Havasupai Woman With Baby

Indians - Havasupai -

1501-0414-0000

Havasupai Dance after Rodeo

Indians - Havasupai -

1501-0417-0000

Havasu Creek Travertine Pools

Indians - Havasupai -

1501-0416-0002

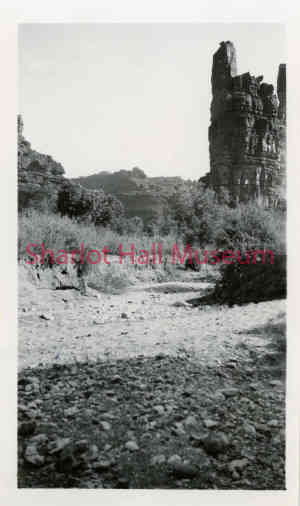

Havasupai Canyon

Indians - Havasupai -

1501-0416-0003

Havasupai Dwelling

Indians - Havasupai -

1501-0415-0002

Havasupai Woman & Baby

Indians - Havasupai