Pima Indian Twined Storage Baskets

Indians - Pima

4X38X8

-

1507-1303-0000

-

1507-1304-0001

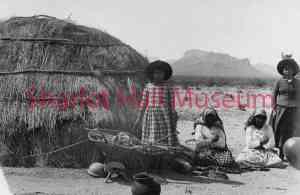

Pima Indian Women Outside a Wickiup

Indians - Pima -

1507-1304-0003

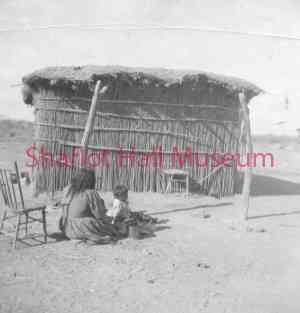

Pima Indian Wickiup

Indians - Pima -

1507-1304-0004

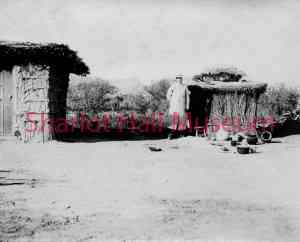

Pima Indian Wickiup and Ramada

Indians - Pima -

1507-1305-0002

Pima Indian Woman Grinding Corn

Indians - Pima -

1507-1305-0005

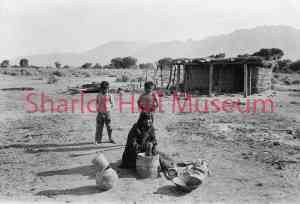

Pima Indian Reservation

Indians - Pima -

1507-1305-0006

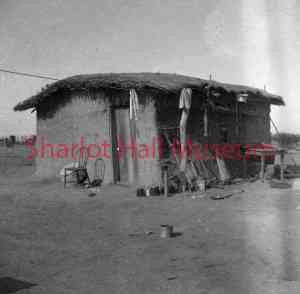

Pima Indian Home

Indians - Pima -

1507-1305-0007

W. Scott Smith at a Pima Indian Reservation

Indians - Pima -

1507-1306-0001

Pima Indian Woven Baskets

Indians - Pima -

1507-1306-0002

Pima Indian Rod

Indians - Pima -

1507-1306-0004

Pima Indian Woven Basket

Indians - Pima -

1507-1307-0000

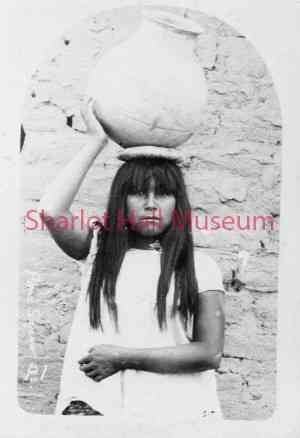

Pima Indian Woman with Olla on Her Head

Indians - Pima