By Stan Brown

Before the founding of Prescott in 1863, Apache raids on ranches and wagon trains occurred in the southern part of what would become the Arizona Territory. Mining between the Gila River and the Mexican border brought new investors and laborers. To protect these settlers, military posts were built and, in 1861, a skirmish at Apache Pass in the Chiricahua Mountains brought Cochise and his warriors into a full scale conflict with the Americans. That same year, the Civil War broke out, and the soldiers left their frontier posts to fight the Confederates back east. The Indians concluded that their intensified raids during the 1850s had finally won them a victory, causing the white men to withdraw. The Apache, Yavapai and Mohave took heart and became more ferocious than ever.

While the Civil War raged in 1862, a well-seasoned gold prospector appeared in Arizona. Joseph Reddeford Walker was over 6 feet tall and strong, 200 pounds of bone and sinew to help him break trail along the rivers of the Southwest. Now 63, he had been a beaver trapper since his early 20s. For many years, he had explored the western mountains with his friend, Kit Carson, honing his gifts of good judgment, strong will, nimble footing and physical strength. They both became guides on a famous John C. Fremont mapping expedition.

Walker was now leading a group of gold prospectors from California into New Mexico, exploring the headwaters of the Gila River in what is now southwestern New Mexico. At the time of their trek following the Gila westward, President Abraham Lincoln signed an act separating the Territory of Arizona from New Mexico (Feb. 24, 1863) in a vertical split rather than the original horizontal proposal. But, politics was not of interest for the Walker Party; their sites were set on the mountains north of the Gila where they hoped to find gold. They passed through Tucson in April and soon reached the Pima and Maricopa Indian villages where they were provided with supplies and native guides.

The Walker party continued west until they came to a tributary to the north leading to the mountains. The Indians called the tributary "Haviamp" meaning "place of big rocks and water." The men molded that sound into Hassayampa.

Suddenly a band of Yavapai Indians appeared "within 10 paces," looking ferocious with painted bodies. One of the prospectors, Daniel Conner, kept a diary and later published their travel adventures. He wrote, "These naked, barbarous wretches sneak out of their holes as insidiously as so many rats, and are not entitled to a consideration more dignified than that which is accorded to the rats and mice about the city livery stable."

Such ugly attitudes set the tone for most white settlers and revealed the void in their understanding of the native culture. The Yavapai made threats regarding any further advance of the white men into their lands. The Walker party's Indian guide, Irataba, tried to talk them into turning back. When they insisted on proceeding, the guide and his warriors left in the night. With great caution, the party continued up the Hassayampa and established a camp about 5 miles from what would later become Prescott. They proclaimed the area a mining district and made a compact as to how each member of the party would be assigned mining claims.

In May 1863, they returned to the Pima villages for supplies. On the way, they joined a group of prospectors from California led by Abraham Peeples with mountain man, Pauline Weaver, their guide. A Gila River rancher, King S. Woolsey, also joined them. Woolsey had recently settled the Agua Caliente ranch and was known for his bravery in fighting off Indian raiders. Woolsey was one of the first to make a gold claim in the Walker district and the gold rush was on. The Peeples and Walker parties shared the mining districts around Prescott, becoming the first whites to settle in the newly established Yavapai County. Miners and ranchers now came from far and wide and began staking out substantial claims, building log houses and laying in food from hunting expeditions while at the same time prospecting for gold.

While hunting, there were encounters with lone Indians, and this sometimes resulted in trade but usually it called for careful avoidance. An open war between the miners and the Yavapai and Apache had not yet been declared and the white men were wise enough not to assert their belief that "the only good Indian is a dead Indian."

Companies of the California Infantry and Cavalry had set up a military post in Val de Chino (Chino Valley) to offer protection for the new territorial government, the settlers and miners. It was named Whipple Barracks to honor Maj. General Amiel W. Whipple who had surveyed the route across northern Arizona and, who had since been killed in the Civil War at the battle of Chancellorsville, Va. In May 1864, the temporary territorial capital was moved to a permanent location on Granite Creek. In the meantime, the new government officials and citizens met to establish a town, which they named Prescott to honor an eastern historian, William Hickling Prescott, well known for his books about the Aztecs. It was erroneously believed the Aztecs had been the first settlers in the region.

This growing intrusion of miners and ranchers into Yavapai lands and bordering on Tonto Apache territories brought an immediate response from the Indians. All of this "invasion" had taken place in only one year and was rapidly escalating! An all-out war with the Apache and Yavapai Indians was imminent.

Next week: The war erupts with devastating results.

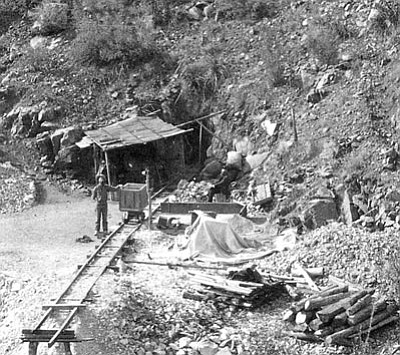

Sharlot Hall Museum/Courtesy photo<br>Catoctin Mine in the Hassayampa District was one of eventually hundreds of mines in Yavapai County.