By Mick Woodcock

In Part One last week, we learned something about Amasa G. Dunn, an early Prescott pioneer, businessman and lawman. In 1869 he had a horrible year. 1870 would be worse.

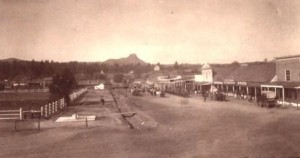

The November 11, 1870, Weekly Arizona Miner lamented, “Nothing displeases us more than to have to record loss of life, by violence, in our town, and but for the fact that it is our plain duty to make a faithful record of such serious matters, we would not do so. Such being the case we must now send out the news that A. G. Dunn, an old citizen of this town, was shot and killed by Jas. A. Simpson.” The notion of “an old citizen of this town” is charming. The town of Prescott itself was barely six years old at that point; A. G. Dunn, however, had been here from the start.

The November 11, 1870, Weekly Arizona Miner lamented, “Nothing displeases us more than to have to record loss of life, by violence, in our town, and but for the fact that it is our plain duty to make a faithful record of such serious matters, we would not do so. Such being the case we must now send out the news that A. G. Dunn, an old citizen of this town, was shot and killed by Jas. A. Simpson.” The notion of “an old citizen of this town” is charming. The town of Prescott itself was barely six years old at that point; A. G. Dunn, however, had been here from the start.

The killing occurred on Election Day — November 8th. The reason wasn’t politics, though. The paper said the animosity between Dunn and Simpson “started on account of a woman.”

Not much is known about Simpson or how or when he and Dunn first crossed paths. But whatever happened, Dunn became determined to kill Simpson, and he made no secret of his plan. The newspaper story continued: “Dunn and another man went to Simpson’s place on Willow Creek, about three miles from town, some time ago, and opened fire on Simpson.” Simpson escaped this assault unharmed, and thereafter apparently tried to avoid Dunn.

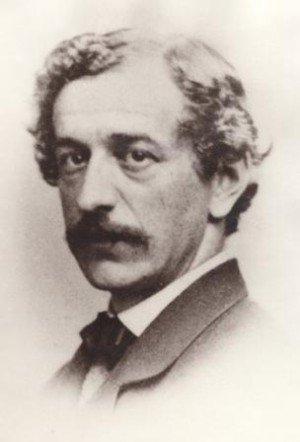

On Election Day, Dunn was at the polls all day, working on behalf of Richard McCormick’s campaign for territorial delegate to Congress. The newspaper continues the story: “He [Dunn] had drank considerable, his worst passions became aroused, and he told a leading McCormick man that he was going to kill Simpson, Simpson was apprised of this, and on being asked, by Governor Safford, why he was not at work, electioneering for McCormick, he gave as his reason for not doing so, the threat which Dunn had made, and his repugnance to getting into trouble.”

On Election Day, Dunn was at the polls all day, working on behalf of Richard McCormick’s campaign for territorial delegate to Congress. The newspaper continues the story: “He [Dunn] had drank considerable, his worst passions became aroused, and he told a leading McCormick man that he was going to kill Simpson, Simpson was apprised of this, and on being asked, by Governor Safford, why he was not at work, electioneering for McCormick, he gave as his reason for not doing so, the threat which Dunn had made, and his repugnance to getting into trouble.”

Later on, as Dunn was no longer around to tell his side of the story, Simpson gave his explanation of the events leading to Dunn’s death. That evening, as Simpson told the story, he was on horseback, heading home when he recognized an inebriated Dunn “loitering” on Cortes Street. Dunn challenged him: “Is that you, Simpson?” When Simpson answered “Yes,” Dunn drew his pistol. Simpson leveled his Sharp’s rifle. Both men fired as they advanced on each other, until they were no more than a few feet apart.

Once again, Dunn failed to hit Simpson. The shootout ended when: “Dunn fell dead, after having received four shots — three from the rifle, and one from a six-shooter, which Simpson drew on account of the machinery of his gun refusing to work.”

The newspaper continued its lament: “Deceased came to this Territory in the latter part of ’63, or early in ’64, we disremember which, and has ever been looked upon as a dangerous man when in liquor. But, he was industrious, and managed to accumulate some property. We believe he was a native of New York. He leaves a wife and daughter. Simpson, the slayer of Dunn has not been long been a resident of the Territory, consequently, we know very little regarding him, further than that his was his first difficulty in the Territory. The case is now undergoing examination, and we forbear further remarks.”

The woman at the center of Dunn’s hatred of Simpson — Dunn’s younger wife, Virginia? His 16-year-old daughter, Mary? Someone else, altogether? Sadly, we don’t know.

Virginia, for her part, after six months of mourning, married the hired hand John Couch, whom she had probably nursed back to health when he was shot in an ambush two years earlier while in the service of her husband.

If Simpson, 35 years old at the time, had been pursuing the 16-year-old Mary, there is no record of them ever marrying.

The outcome of the case against Simpson? Immediately after he killed A. G. Dunn, he surrendered to the sheriff, and was locked up briefly. But, since he had no previous trouble in Arizona Territory and the circumstances of the case indicated that he had fired in self defense, the court released him on $5,000 bail. There is no record of any further action in the case. By June of 1871, he was operating a “saddle train” from Prescott to Bradshaw.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at www.sharlothallmuseum.org/library-archives/days-past. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles to dayspastshmcourier@gmail.com. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-277-2003, or via email at dayspastshmcourier@gmail.com for information.