By Barbara Patton

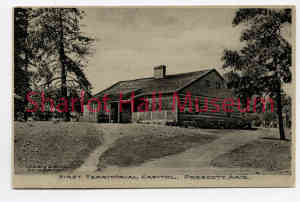

How did a deteriorating log house whose history was covered in clapboards and neglect become a museum for territorial history?

The building, built in 1864, was home for the first two territorial governors. When the capital moved to Tucson in 1867, the governor’s private secretary, Henry Fleury, purchased the house. He defaulted on the mortgage, but was allowed to live in it until his death in 1895. After Fleury, the residence changed hands a couple of times before owner Joseph Dougherty converted it to a duplex and a rental property. To give the building a Victorian look, he covered the ponderosa logs in clapboards and added a dormer and side porch.

Meanwhile, Sharlot Hall, who had visited Fleury when she was a teenager and heard his stories of the early days, voiced her long-felt interest in the place in a 1907 speech at the Elks Club Theater. She stated that the “Old Governor’s House” (as she thought it should be called) was “a priceless relic” and should be restored. However, nothing was done until 1917 when the state purchased the building and turned it over to the City of Prescott with the stipulation it become a museum, but did not provide funds to do so. It was another ten years before the city granted a lifetime lease of the building to Sharlot in 1927.

Meanwhile, Sharlot Hall, who had visited Fleury when she was a teenager and heard his stories of the early days, voiced her long-felt interest in the place in a 1907 speech at the Elks Club Theater. She stated that the “Old Governor’s House” (as she thought it should be called) was “a priceless relic” and should be restored. However, nothing was done until 1917 when the state purchased the building and turned it over to the City of Prescott with the stipulation it become a museum, but did not provide funds to do so. It was another ten years before the city granted a lifetime lease of the building to Sharlot in 1927.

During those years, Sharlot was helping her elderly father on their farm in Dewey and didn’t have the time or energy to pursue her dream of moving into and restoring the Old Governor’s House.

After Sharlot’s father, James Hall, died in September 1925, she was finally able to realize her dream. On May 28, 1927, she wrote a letter to Prescott City Attorney, Joseph A. West, describing why she thought the old house should be turned over to her and what she planned to do with it.

In this letter, Sharlot described two major goals for the Old Governor’s House. First, she wanted to restore the building and make it a museum. Second, she would use the museum to store and display her personal collection of artifacts. To accomplish these goals, she wanted a lifetime lease on the property and freedom to develop the museum as she saw fit. She also wanted assurances her work would continue after her death.

In this letter, Sharlot described two major goals for the Old Governor’s House. First, she wanted to restore the building and make it a museum. Second, she would use the museum to store and display her personal collection of artifacts. To accomplish these goals, she wanted a lifetime lease on the property and freedom to develop the museum as she saw fit. She also wanted assurances her work would continue after her death.

On June 7, 1927, Prescott Mayor, E.C. Seale, signed an agreement between the city and Sharlot Hall. It included Sharlot’s letter and the city’s agreement to her stipulations, plus a promise to help with basic utilities and upkeep. The city would allow Sharlot to develop the building into a museum and make it her home for the rest of her life. The document also mentioned Sharlot’s extensive collection of artifacts, valued at $10,000 (approx. $150,000 in today’s dollars) which she would keep in the museum.

However, Sharlot couldn’t move into the Old Governor’s House immediately. That fall, she developed serious back issues and traveled to Boston to see a medical specialist. While in the East, she visited the Old Wayside Inn in Sudbury, Massachusetts. She was very impressed - - “I found Henry Ford doing with the Wayside Inn exactly what I have dreamed for thirty years of doing with the old house in Prescott.” Of course, she acknowledged she didn’t have the money that Ford could spend on the project.

Back in Prescott in late 1927, Sharlot hoped to spend time in the house starting in January 1928; however, a harsh winter pushed her plans to March, when she finally moved in. Next week, read more about Sharlot’s plans and the years of hard work to develop a museum.

Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at archives.sharlothallmuseum.org/articles/days-past-articles/1. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Research Center reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.