By Susan Cypert

From 1954, when she first ran Glen Canyon, Katie Lee stayed on the road for the next ten years, crisscrossing America in a 1950’s Thunderbird coupe, singing in popular nightclubs and returning fifteen times to Glen Canyon, often paying her way on the trips by singing folk songs for tourists.

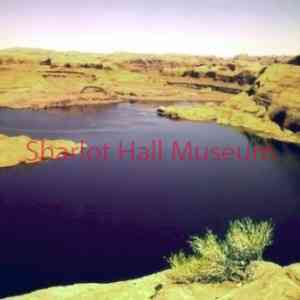

Back then the Glen Canyon was virgin territory known only to a few. It was also considered to be one of the most beautiful canyons in North America. Lee and her friends probably came to know the canyon the best; they explored many of its 200 plus side canyons (naming some 25 of them), crawled through ancient Indian caves and camped and sang on starlit sandbars.

Since the beginning of her river runs, she had heard about the Bureau of Reclamation’s proposal to dam the Glen Canyon. She passionately opposed the dam and inundated Senator Barry Goldwater with letters of protest.

Since the beginning of her river runs, she had heard about the Bureau of Reclamation’s proposal to dam the Glen Canyon. She passionately opposed the dam and inundated Senator Barry Goldwater with letters of protest.

The damming of the Colorado River at Glen Canyon would come to be seen as the ecological crime of the 20th century. According to the article, “The Starlet’s Passion” by Leo Banks in the Tucson Weekly January 14- 20, 1999, “Few environmental issues are richer in irony and political gamesmanship than the decision to build this dam. Its origins are in the long running feud between Western States over use of Colorado River water.” The tug of war between the upper basin states of Utah, Wyoming, Colorado and New Mexico and the lower basin states of California, Arizona and Nevada led to the passage of the Colorado River Compact in 1922. Later, the upper basin states pushed for and got passed the Colorado River Storage Project of 1956, which provided money to build several dams and irrigation projects.

Among those dams was one in Echo Park, Utah, on the Green River, which would have backed water up into Dinosaur National Monument. David Brower, founder of the fledgling Sierra Club, told the government that Glen Canyon was a better site for a dam and that he wouldn’t oppose plans to build there. According to the Tucson Weekly article, he essentially traded Glen Canyon away, as allegedly did Barry Goldwater, who voted in favor of the dam. In the years after, both Brower and Goldwater expressed profound regret and reversed their positions. According to the same article, Senator Goldwater said if he could take back a single vote in his long career, it would be the one he cast in favor of the dam.

Among those dams was one in Echo Park, Utah, on the Green River, which would have backed water up into Dinosaur National Monument. David Brower, founder of the fledgling Sierra Club, told the government that Glen Canyon was a better site for a dam and that he wouldn’t oppose plans to build there. According to the Tucson Weekly article, he essentially traded Glen Canyon away, as allegedly did Barry Goldwater, who voted in favor of the dam. In the years after, both Brower and Goldwater expressed profound regret and reversed their positions. According to the same article, Senator Goldwater said if he could take back a single vote in his long career, it would be the one he cast in favor of the dam.

In 1955, while engineers finalized plans for the dam, Katie and a few archeologists helped map the canyon’s soon-to-be-lost topography. They floated the Colorado, exploring hundreds of side streams, climbed cliffs and squeezed through slot canyons.

In 1955, while engineers finalized plans for the dam, Katie and a few archeologists helped map the canyon’s soon-to-be-lost topography. They floated the Colorado, exploring hundreds of side streams, climbed cliffs and squeezed through slot canyons.

But on October 15, 1956, the first dynamite charge went off, blasting an ugly hole in the wall of the canyon, and water began to drown the inlets and side streams, although it took seven years to fill the canyon. Katie ignored the “Keep Out” signs and decided to “drink until I was drunk with it…because this was going to have to last me the rest of my life…and it has.” She sang her last song in Music Temple in 1962, the year before the diversion tunnels were closed and the Colorado River started filling what would become Lake Powell. She never got over the drowning of Glen Canyon. It haunted her like an execution.

Next week Katie becomes an activist.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at https://www.sharlot.org/articles/days-past-articles.l. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.