by John L. Vankat

Repeat photography is an eye-catching way to bring history alive. It involves collecting historical photographs, finding the sites where the early photographers stood and reshooting the same scenes. Each repeat photograph is then compared to the historical photograph to reveal how the site has changed from the past to the present. This helps us understand both the past and present, as well as predict and plan for the future.

Repeat photography is an eye-catching way to bring history alive. It involves collecting historical photographs, finding the sites where the early photographers stood and reshooting the same scenes. Each repeat photograph is then compared to the historical photograph to reveal how the site has changed from the past to the present. This helps us understand both the past and present, as well as predict and plan for the future.

Over the last 8 years, I precisely repeated 125 historical photographs of landscapes on and around northern Arizona’s beautiful San Francisco Peaks. These pairings of historical and repeat photographs are presented in my recently published book, The San Francisco Peaks and Flagstaff Through the Lens of Time (Soulstice Publishing).

The earliest photographs in the San Francisco Peaks’ region were taken in 1867 by professional photographer Alexander Gardner, who was part of a federal survey exploring possible railroad routes to the West Coast.

When the railroad was built through Flagstaff in 1881, it enabled photographers to visit northern Arizona. Their photographs revealed the eye-catching beauty and diversity of the region around the San Francisco Peaks, extending from downtown Flagstaff to the 12,621-foot summit of Humphreys Peak, Arizona’s highest elevation.

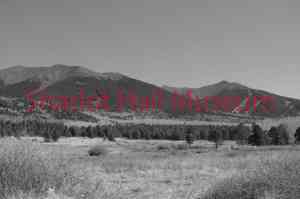

The accompanying historical photograph is from the collections of the Sharlot Hall Museum. It dates to around 1900 and is by an unknown photographer. The photo shows ranch buildings in Hart Prairie, which is immediately west of the San Francisco Peaks. Humphreys Peak is near the left side of the photograph, and Agassiz Peak, Arizona’s second tallest mountain, is on the right. The land in the photograph is now within the Coconino National Forest.

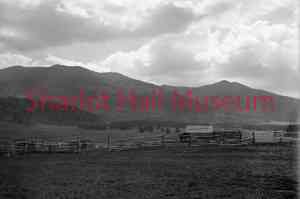

My repeat photograph, taken from the same site at 8600 feet elevation, shows the ranch buildings and fencing have been removed, and ski runs have been built on Agassiz Peak. Note that reduced livestock grazing has led to more shrubs and herbs in the foreground.

An even more evident change is the increase of trees in the former grasslands beyond the ranch site. This ingrowth began in the mid-19th century when livestock grazing reduced competition for tree seedlings and also reduced the herbaceous fuels that formerly spread tree-killing wildfires.

The repeat photograph also shows that trees have increased within forests upslope from the grassland. This is largely the result of the decades-long policy of the U.S. Forest Service to eliminate forest fires, which formerly had maintained more open forests but were considered damaging.

The trends of increased shrubs and trees and decreased grassland will continue into the future unless land management in this area changes from suppressing all fires to intentionally setting prescribed fires and managing naturally occurring ones. Fires at these elevations are essential for maintaining grasslands and for returning forests to their natural, more open state. Without management fires to decrease tree densities, it is only a matter of time before unnaturally large, highly destructive forest fires burn this area and dramatically change its ecology.

If you want to know more, come listen to John L. Vankat’s talk on August 5 at the 20th Annual Western History Symposium to be held at the Phippen Museum of Western Art.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at www.archives.sharlothallmuseum.org/articles/days-past-articles/1 The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org Please contact SHM Research Center reference desk at 928-277-2003, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.