By Kathy Krause

The following article was compiled and edited by Kathy Krause and taken from various articles originally written by Richard Gorby published in the SHM Day Past Arcihves.

Most people in the Prescott area are familiar with Groom Creek and even Groom City, but know nothing about Robert Groom. But we can all be thankful for something he gave us 148 years ago: downtown Prescott.

Chosen by the governor of the newly established Arizona Territory to lay out the town in the spring of 1864 was Groom, the only available surveyor at the time. He was apparently given carte blanche in planning "his town," possibly because he had been overruled in his choice of location; Groom wanted the capital built at the beautiful Point of Rocks in Granite Dells.

Working at a table in a log cabin on Montezuma Street later known as "Old Fort Misery" (moved to Sharlot Hall Museum grounds in 1936), he designed his town. Using an old-fashioned spyglass and a tripod he built himself, he designed it beautifully - the way he thought a town should be. His streets were 80 feet wide, wider than most in the country. Most towns then and even later thought streets wide enough for two buggies to pass were sufficient.

And his central plaza! More than twice the size of most town squares in the country, the plaza was beautiful. The trees surrounding it were cut down almost immediately to make room for the sale of lots for future business buildings, but the plaza itself was left (for a while) covered with stately pines and junipers.

A public meeting was held on "Monday evening, May 30, 1864, for the purpose of considering and adopting the best mode of disposing of lots in the proposed town, to those wishing to purchase under the recent Act of Congress." Of many resolutions adopted that evening were "that at least one square in the proposed town site should be reserved for a public plaza," and "that a Mass Meeting be held at Prescott on Monday, July 4, 1864, at noon, to celebrate the 88th anniversary of American Independence, and properly to inaugurate the new town, a fresh evidence of American progress and prosperity."

Thus on July 4, 1864, Prescott held its first Fourth of July celebration. Like all celebrations should be, it was happy and exciting and, like all Prescott celebrations should be, it was held on Prescott's new plaza. Prescott was officially only 35 days old. On the southeast corner (across from the present downtown post office), a 144-foot pine staff was erected for the Stars and Stripes, hoisted at dawn (the pole remained on the plaza for some time thereafter). At 9:30 a.m., the Fort Whipple Garrison, commanded by Major E. B. Willis, was reviewed by the governor. At noon, on a platform between two large pine trees, Governor John Goodwin and Secretary Richard McCormick and their staff took their seats. After a prayer by Rev. H. W. Read, there was music by Lucien Bonaparte Jewell, later founder of the Prescott Brass Band, but now with only two violins and a banjo playing "The Star-Spangled Banner" as the opening number (it was not named our official national anthem until 1931). The oration by the Secretary of the Territory, Richard McCormick, was quite long.

About 400 men, mostly miners from the area and almost all of them under 30 years of age, "laid there on the ground with pistols and butcher knives buckled around them, quite indifferent about the 4th of July" according to one report. They "for the most part were dressed most any way ... old shoes, half-soled and worn out ... patched trousers ... remains of a checked shirt and what was once a felt hat that had been mended so often that it was of many colors."

There were no women present that day. It was not that women had not been invited; it was just that Prescott had no women! There were a few living at Fort Whipple, but there is no record of their attendance at the celebration.

Three meals were prepared and served that day by the Juniper House, Prescott's first "restaurant," which had been started by George W. Barnard under the shade of a friendly juniper, but moved into a building by the July 4 celebration. The Arizona Miner newspaper listed the bill of fare but quoted no price for the meals. Doubtless they were too expensive for many of the attendees who retreated to their own abode for a pot of frijoles.

The Roundtree Saloon provided "refreshment" on the plaza and was described by Charles Genung (who was there that day): "It was built of cloth and timber - a small wagon sheet stretched over a pole which rested in the forks of two upright posts. The bar fixtures consisted of one 10-gallon keg of what we called whiskey; a half dozen tin cups and a canteen of water. The 'Pod' and Dickson's Saloon were crowded with customers."

The Arizona Miner of July 6, 1864, reported: "We will not say how much whiskey was disposed of. Nobody was hurt, although the boys waxed very merry, and some of them very tipsy, and there was no little promiscuous firing of revolvers."

Prescott's Fourth of July celebrations are still held on the plaza, even though they might not be quite as exciting as the first.

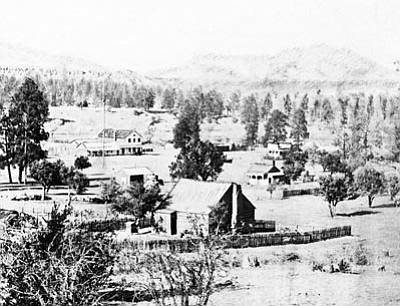

Sharlot Hall Museum/Courtesy photo

“Downtown” Prescott, circa 1869. If you look closely to the left of the white two-story building, you can see the 144-foot pine flagstaff (no flag on this photo), which was erected in 1864 on the plaza for the first Fourth of July celebration. The two-story white building is the Diana Saloon, which stood on the corner where the Hotel St. Michael stands today.