By Bob Baker

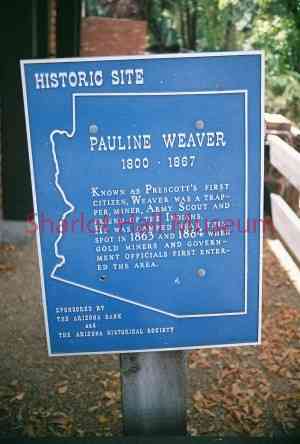

In the early 1800s, Yavapai and Apache Indians inhabited the wilderness that became the Arizona Territory. Only a few frontiersmen dared travel there to trap beaver, hunt game and explore the area. Perhaps the earliest of them was Pauline Weaver.

In the early 1800s, Yavapai and Apache Indians inhabited the wilderness that became the Arizona Territory. Only a few frontiersmen dared travel there to trap beaver, hunt game and explore the area. Perhaps the earliest of them was Pauline Weaver.

When Weaver arrived in Arizona in 1830 from California, he had traveled all over California trapping beaver and trading with Indian tribes. While he was primarily a trapper, he was also a prospector who recognized “pay dirt” (gold deposits), having discovered several placer gold deposits in California.

In May 1863 at Fort Yuma, Arizona Territory, Mr. A. H. Peeples hired Weaver to guide the Peeples Party that discovered rich gold deposits at the Weaver and Rich Hill diggings south of present day Yarnell. Some weeks later, Weaver attempted to make a peace treaty among the hostile tribes that would allow white men and members of other tribes to travel freely across each other’s lands.

On October 27, 1929, in her address at Weaver’s reburial in Prescott, Sharlot Hall explained “.. He and Moss (John Moss, an ex-soldier) divided the whole western region into hunting grounds and assigned them to different tribes and families; binding each to keep within their own lines except at stated times when they met at points designated for trade and barter. Since few Indians spoke any English, he gave them all one password with which to greet white travelers as a token of their peaceful intent. This was his own name and the word “tobacco,” an article Indians were keen to buy or beg from whites.” According to Mr. Charles B. Genug, an early pioneer in California and Arizona, the actual password was “Powlino, Powlino, tobacco.”

This peace was short-lived as many white newcomers had no knowledge of the treaty or chose to ignore it. This engendered general distrust among the Indian tries and led to renewed conflicts.

This peace was short-lived as many white newcomers had no knowledge of the treaty or chose to ignore it. This engendered general distrust among the Indian tries and led to renewed conflicts.

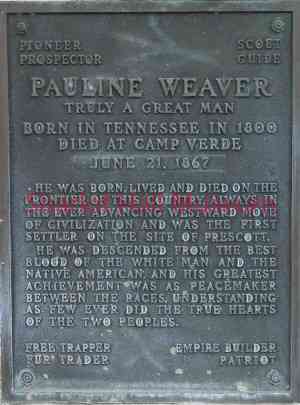

In the Argonaut Tales, Pauline Weaver is described in 1864 as “… well advanced in years, robust and hardened by frontier life, adventure and experience. In stature he was over six feet in height, broad-shouldered, and straight as an arrow. His eyes were black, nose on the aquiline order, and large mouth. His mingled black and gray hair fell in straggling locks to his shoulders, and his black grizzled beard flowed well down his broad chest. His features were strong and prominent, and his deep bass voice had the blast of a fog horn…"

Due to his vast knowledge of the area and the Indian tribes, Weaver was often employed as a scout for the U.S Army. While serving at Fort Whipple, he lived in a tent along Granite Creek rather than at the Fort. While serving at Camp Lincoln (now Camp Verde), he died on June 21, 1867 of congestive chills and was buried in the camp cemetery. In 1891, Camp Lincoln was abandoned, and his remains were shipped to San Francisco for burial in the National Military Cemetery.

During the 1920’s, a movement began to bring his remains home. Local attorney Alpheus H. Favor enlisted the help of the Yavapai-Mohave Boy Scouts Council in a fundraising educational program in the county schools and induced the Arizona State Legislature to pay for an appropriate monument. The school children donated enough to cover the transportation of Weaver’s remains back to Prescott.

During the 1920’s, a movement began to bring his remains home. Local attorney Alpheus H. Favor enlisted the help of the Yavapai-Mohave Boy Scouts Council in a fundraising educational program in the county schools and induced the Arizona State Legislature to pay for an appropriate monument. The school children donated enough to cover the transportation of Weaver’s remains back to Prescott.

On October 27, 1929, Pauline Weaver’s remains were returned and buried on the grounds of the Territorial Museum (now Sharlot Hall Museum). A large granite boulder bearing a bronze plaque honoring his life marks his final resting place.

"Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at archives.sharlothallmuseum.org/articles/days-past-articles/1. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Research Center reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.