By Bob Harner

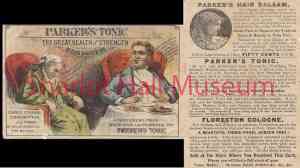

“The Greatest Medical Triumph of the Age…[O]ne dose effects such a change of feeling as to astonish the sufferer.” These quotes from an ad for Tutt’s Pills in the January 6, 1886 Arizona Weekly Journal Miner are not the most outrageous claims made by patent medicine manufacturers; in fact, they are typical.

Popularly referred to as “snake oil” and dating back to America’s first settlers, unregulated medications containing “secret” ingredients reached peak popularity in the mid and late 19th century. Originally, they were local products concocted in kitchens. But, they became major national businesses when the transcontinental railroad, low postal rates, the growth in daily newspapers in need of advertisers and the birth of professionally written advertising copy converged in the 1800’s.

Patent medicine contents were not patented, as that required revealing their ingredients. Instead, manufacturers were more interested in copyrighting various trademarks, including bottle shape and design, label design and printed slogans. No one was required to prove their products either safe or effective; generally, they claimed to cure whatever ailments were most prevalent at the time, sometimes changing what afflictions they affected as the “popularity” of a disease came and went. Given common medical practices of the time (bleeding and purgatives) and the long history of home remedies, the promises of quick and painless cures were irresistible to many.

Patent medicine contents were not patented, as that required revealing their ingredients. Instead, manufacturers were more interested in copyrighting various trademarks, including bottle shape and design, label design and printed slogans. No one was required to prove their products either safe or effective; generally, they claimed to cure whatever ailments were most prevalent at the time, sometimes changing what afflictions they affected as the “popularity” of a disease came and went. Given common medical practices of the time (bleeding and purgatives) and the long history of home remedies, the promises of quick and painless cures were irresistible to many.

Prescott was no exception. The front page of the Journal Miner mentioned earlier contained ads for five different patent medicines, including Ely’s Cream Balm which promised to cure “catarrh, cold in head, hay fever, deafness, headache.” Tutt’s Pills claimed “25 years in use” for the treatment of a “torpid liver,” the symptoms of which involved almost every discomfort imaginable, including “low spirits and dots before the eyes.”

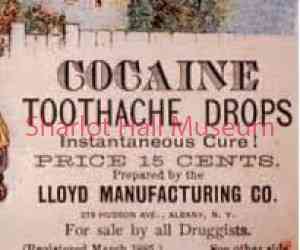

Many popular concoctions included large amounts of alcohol, sometimes combined with opium or cocaine. Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters, a national best-seller, was 47% alcohol (94 proof) and was sometimes sold by the glass when whiskey supplies were low. The company’s Pittsburgh headquarters employed 1000 workers and distributed a popular annual almanac.

Certain key terms were popular in advertising, including claiming “vegetable” ingredients (such as a June 25, 1895 Journal Miner ad for Hood’s Sarsaparilla Cures), Native American origins (Kickapoo Indian Sagwa was a favorite) or a “foreign” connection. The Journal Miner carried ads for Mesmin’s French Female Pills (“The Ladies’ Friend”), Dr. Salfield’s Rejuvenator (“The Great English Remedy” nerve tonic), and St. Jacob’s Oil (the “great German” cure for rheumatism).

Certain key terms were popular in advertising, including claiming “vegetable” ingredients (such as a June 25, 1895 Journal Miner ad for Hood’s Sarsaparilla Cures), Native American origins (Kickapoo Indian Sagwa was a favorite) or a “foreign” connection. The Journal Miner carried ads for Mesmin’s French Female Pills (“The Ladies’ Friend”), Dr. Salfield’s Rejuvenator (“The Great English Remedy” nerve tonic), and St. Jacob’s Oil (the “great German” cure for rheumatism).

Some claims were merely outrageous. A Journal Miner ad for Cupidene promised to “quickly cure you of all nervous or diseases of the generative organs, such as Lost Manhood, Insomnia…Unfitness to Marry.” Others were potentially dangerous. One Journal Miner ad stated that Golden Medical Discovery guaranteed a cure for consumption (tuberculosis) “by this God-given remedy, if taken before the last stages of the disease are reached.” Another ad offered a lengthy testimonial by Mrs. J.P. Bell from Kansas who swore three bottles of Dr. Miles’ Heart Cure “completely cured” her after six years of heart disease.

In addition to their uselessness as medications, patent medicines (with their alcohol and narcotic contents) were frequently the source of serious addictions, causing them to become a target for the growing temperance movement. Hard-hitting stories by investigative reporters for national magazines (Collier’s in particular) and the passage of drug regulations ultimately led to their decline, although some lasted surprisingly far into the 20th century (Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters remained popular during Prohibition). Others transformed their purpose and ingredients. Coca-Cola evolved from a cocaine-laced medication to a “soft drink.” Similarly, Dr. Pepper and Hires Root Beer began as patent medicines.

Finally, there’s Dr. Miles’ Compound Extract of Tomato – known today, generically, as ketchup.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at https://www.sharlot.org/articles/days-past-articles.l. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Research Center reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.