By Ray Carlson

Arizona became part of the United States as a result of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo that ended the Mexican-American War in 1848. The Gadsden Purchase, five years later, added additional territory needed to build a transcontinental railroad across the Deep South. The negotiations for the purchase also attempted to resolve conflicts with Mexico. The War evoked mixed reactions in the East with critics like Abraham Lincoln wondering what the US achieved. As a congressman, Lincoln suggested that President Polk’s “mind is tasked beyond its power.” He suggested the President had a desire for "military glory—that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood." Obviously, President Polk could claim that he had greatly increased the country’s land mass, but was the land of any value? From the standpoint of Easterners, southern Arizona was a desert that, at best, provided an arduous and life-threatening route to the West called the Southern Emigrant Trail.

John Woodhouse Audubon, son of the well-known naturalist, wrote a diary describing his journey on this Trail in 1849. Audubon’s trip had problems from the beginning as cholera struck, killing ten men, and leaving several including Audubon sick for several days. Over half quit including the leader. Audubon took over as leader of the smaller group that finally headed toward the Gold Rush in California. The bulk of their money was stolen, but they eventually made it to western Arizona.

John Woodhouse Audubon, son of the well-known naturalist, wrote a diary describing his journey on this Trail in 1849. Audubon’s trip had problems from the beginning as cholera struck, killing ten men, and leaving several including Audubon sick for several days. Over half quit including the leader. Audubon took over as leader of the smaller group that finally headed toward the Gold Rush in California. The bulk of their money was stolen, but they eventually made it to western Arizona.

Audubon’s most positive term for Arizona was “desolate.” It was a desert with parched, sandy land, almost no game and dried up water holes. He complained that for ten days they had no coffee, almost no meat and lived on bread and water. “Why it is that these Indians settle in this country, I cannot conceive, for even the lizards, in most places innumerable, are scarce here.” On the ninth day, they found some grass for the mules and, on the tenth, some water. Finally, in the evening of the eleventh day, they reached the “Pimos Valley.” The “old Pima chief” came to greet them, showing letters from leaders of government explorations recommending the chief as “honest, kind, and solicitous for the welfare of Americans.” The name “Pima” is close to the phrase for “I don’t know” which is what the residents probably said when they were asked questions by the Spanish.

The “Pima” Villages were an oasis with ample food and water. Most travelers stopped there to trade resulting in the “Pimas” having ample basic goods. They only wanted unusual things. To get food, Audubon had to give up dress shirts, special blankets and flannel shirts which would be torn into strips and sewn together as sashes. Restored, they returned to the inhospitable trail.

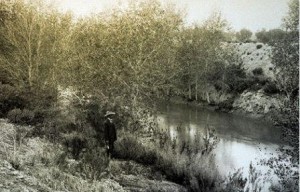

A survey in 1857 indicated there were nine “Pima” villages, each near the beginning of a canal. The canals irrigated farms which supported 4,117 people in this area in the middle of the desert. The canals traced back 3,500 years having been dug by the original residents. Archaeologists called these people Hohokam, a derivation of the “Pima” word Huhugam, which refers to ancestors or “those who are gone.” It’s important to distinguish between Hohokam, an archeological name for these people, and Huhugam, a cultural reference to spiritual ancestors. Recently, the name Ancient Sonoran Desert People has been used by academics to communicate more respect for these ancient people who developed an impressive canal and irrigation system along the Gila, Salt, Santa Cruz, and San Pedro Rivers. This earlier group left the area for unknown reasons over five hundred years ago, and the “Pima” moved into the Gila River area about one hundred years later. Although “Pima” has been used for centuries by the Spanish, Mexicans and Americans, within the group itself, the name Akimel O’odham, which in their language means River People, is more appropriate. Working with sharp sticks and rocks, both the Ancestral People and the Akimel O’odham hand dug canals from the river into the fields gradually adjusting width and depth to create a good water flow. Smaller branches reached into the fields. The engineering of the canals avoided over- and under-saturating the ground. Crops included corn, beans, melon and cotton. About 1700, Spanish missionaries gave them other seeds including wheat which, like cotton, became important for trade.

4,117 people in this area in the middle of the desert. The canals traced back 3,500 years having been dug by the original residents. Archaeologists called these people Hohokam, a derivation of the “Pima” word Huhugam, which refers to ancestors or “those who are gone.” It’s important to distinguish between Hohokam, an archeological name for these people, and Huhugam, a cultural reference to spiritual ancestors. Recently, the name Ancient Sonoran Desert People has been used by academics to communicate more respect for these ancient people who developed an impressive canal and irrigation system along the Gila, Salt, Santa Cruz, and San Pedro Rivers. This earlier group left the area for unknown reasons over five hundred years ago, and the “Pima” moved into the Gila River area about one hundred years later. Although “Pima” has been used for centuries by the Spanish, Mexicans and Americans, within the group itself, the name Akimel O’odham, which in their language means River People, is more appropriate. Working with sharp sticks and rocks, both the Ancestral People and the Akimel O’odham hand dug canals from the river into the fields gradually adjusting width and depth to create a good water flow. Smaller branches reached into the fields. The engineering of the canals avoided over- and under-saturating the ground. Crops included corn, beans, melon and cotton. About 1700, Spanish missionaries gave them other seeds including wheat which, like cotton, became important for trade.

While travelers like Audubon wondered why anyone would want to live in this area, the Akimel O’odham demonstrated that expert irrigation could make this territory not only habitable but comfortable and useful.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at www.sharlothallmuseum.org/library-archives/days-past. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles to dayspastshmcourier@gmail.com. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-277-2003, or via email at dayspastshmcourier@gmail.com for information.