By Bob Harner

After two failed trapping expeditions in present-day Arizona, James Pattie settled into a more sedate (and more lucrative) life with his father, Sylvester, operating the Santa Rita del Cobre copper mines in New Mexico Territory. Unfortunately, this venture also ended in failure when the mine’s assistant manager absconded with most of their money. At the same time, they learned that the Mexican president had ordered all Spanish-born residents to dispose of their property and leave the country. The mine’s Spanish-born owner, who had been renting the mine to the Patties, hoped to sell them the mine. With the loss of their funds, this proved impossible.

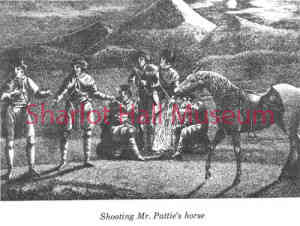

Instead, the Patties used their little remaining money to buy more trapping equipment, obtain a new permit from the New Mexican governor and join a group of about 30 others for another expedition along the Gila. Once in the Arizona wilderness, the group had difficulty finding game and quickly exhausted their food supplies. After being forced to eat all their dogs and six of their horses, they were finally able to hunt enough game to continue.

Instead, the Patties used their little remaining money to buy more trapping equipment, obtain a new permit from the New Mexican governor and join a group of about 30 others for another expedition along the Gila. Once in the Arizona wilderness, the group had difficulty finding game and quickly exhausted their food supplies. After being forced to eat all their dogs and six of their horses, they were finally able to hunt enough game to continue.

After successfully trapping as far as the present Yuma crossing, the group split into two, the majority choosing to return to New Mexico, while the Patties and six others continued into California. This proved to be a disastrous decision, when all their remaining horses were stolen. Desperate, the eight men constructed canoes to transport them and their beaver pelts down the Colorado River, where they assumed they would find a Mexican settlement that could supply them with horses.

Reaching the mouth of the Colorado without finding any settlements, they buried their furs near the river and set off on foot for the California coast. Arriving at the Mission Santa Catalina, they were immediately taken prisoner by Mexican authorities and transported to San Diego to be brought before the governor. The governor, Jose Maria Echeandia, accused them of being spies for the “old Spaniards,” destroyed their pass from Santa Fe (declaring it a forgery) and imprisoned them.

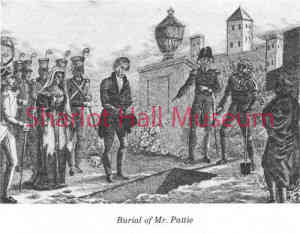

Although treated kindly by his warden, Sergeant Jose Pico, James was kept alone in a cell, cut off from the others until he received a note from his father, written in blood on a scrap of paste board torn from Sylvester’s hat. In the note, Sylvester declared that he was ill and dying. Initially refused permission to see his father, James was finally allowed to attend Sylvester’s funeral after the elder Pattie’s death on May 24, 1827.

The governor’s attitude toward his American prisoners began to soften after using Pattie to translate English documents into Spanish. He allowed some of Pattie’s men to return to the Colorado to retrieve their furs, where they discovered that the river had overflowed its banks, destroying everything they buried.

According to Pattie, his father had brought a supply of smallpox “vaccine” with them from New Mexico. As a bargaining tool with the governor, James offered to use this supply to counter a smallpox outbreak in Northern California. Although much of Pattie’s California account is confirmed by other sources, scholars are highly skeptical of this claim, since smallpox vaccination was common in California at the time.

According to Pattie, his father had brought a supply of smallpox “vaccine” with them from New Mexico. As a bargaining tool with the governor, James offered to use this supply to counter a smallpox outbreak in Northern California. Although much of Pattie’s California account is confirmed by other sources, scholars are highly skeptical of this claim, since smallpox vaccination was common in California at the time.

After briefly joining a local revolt led by Joaquin Solis, Pattie ultimately switched allegiance back to the governor, who finally allowed Pattie to return to the U.S. via Mexico City. In Mexico City, Pattie met with Anthony Butler, the U.S. charge d’affairs, who had received a letter from Martin Van Buren, Andrew Jackson’s Secretary of State, requesting that the Mexican president free the Patties from California imprisonment.

Meeting with the Mexican president, Pattie was given a passport home and partially reimbursed for his losses. Pattie’s misfortunes continued, however, when his stagecoach was robbed. Penniless again, Pattie was provided with money to sail to New Orleans by Isaac Stone, U.S. consul at Vera Cruz. In New Orleans, he met and befriended Josiah Johnston, senator from Louisiana, who paid for Pattie’s steamboat passage upriver to Cincinnati. There, Johnston introduced Pattie to Timothy Flint, local bookstore owner and popular author. After a trip to his grandfather’s home in Augusta, Kentucky, Pattie returned to Cincinnati where he and Flint co-authored Pattie’s best-selling Personal Narrative.

Although the book brought Pattie some fame, it did not bring him fortune. The final historical record of Pattie is the 1833 Bracken County, Kentucky, tax record showing that he owned two horses worth $75. James Pattie’s brief but eventful life likely ended in the Kentucky cholera epidemic of 1833 at the age of 29.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at https://sharlothallmuseum.org/articles/days-past-articles.l. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.