By Dave Lewis

Previously: Spain established its first permanent settlements in Arizona as missions at Tubac in 1752 and twenty years later at Tucson. The name “Arizona” emerged in the 1730s, but it belonged to a small ranching community in Sonora.

In the early 1700s, Spain’s optimism over its foothold in its newly-claimed lands was tempered by hard reality. Native peoples, some of whom were initially friendly and curious, could be pushed only so far in giving up their beliefs and dominion over their lives and lands. Most accommodating were the Pimas who lived alongside the Spaniards, but they rose up in bloody rebellion at times. Apaches were unrelentingly hostile.

Priests such as Fray Kino made some difference through kindness and generosity. Kino crossed Arizona from his missions on the Santa Cruz to the Colorado River safely and virtually alone. He followed the treacherous El Camino del Diablo over blistering desert — roughly along today’s U. S. - Mexico Border. He crossed the Colorado River into California, proving that an overland route was possible. This gave hope to Spain which was intent upon settling California. In 1711, Fray Kino died of natural causes.

Several generations passed before another priest of Kino’s stature served in Arizona. In 1767, Fray Francisco Garces arrived to continue Kino’s good works. Garces traveled extensively, looking for souls to save, sites for missions, and a still-elusive safe and practical overland route to California. He tried Kino’s Devil’s Highway — and decided to keep looking.

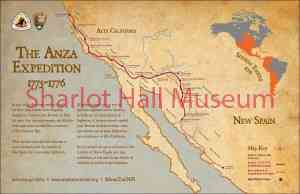

With Tubac and Tucson firmly established, a better route to California emerged. In the early 1770s, Garces helped Juan Bautista de Anza explore a route northwest from Tubac along the Santa Cruz to the Gila and down the Gila to the land of the Yumas and a Colorado River crossing that would later bear that tribe’s name. Comfortable with that route, in 1775 Garces and de Anza set out with a party of 240 settlers —men, women, children (some born along the way), and more than 1000 head of horses, mules and cattle. Crossing into California and toward the Pacific, the party went north to establish a new settlement at San Francisco. “Vayan Subiendo!” was the rallying cry.

With Tubac and Tucson firmly established, a better route to California emerged. In the early 1770s, Garces helped Juan Bautista de Anza explore a route northwest from Tubac along the Santa Cruz to the Gila and down the Gila to the land of the Yumas and a Colorado River crossing that would later bear that tribe’s name. Comfortable with that route, in 1775 Garces and de Anza set out with a party of 240 settlers —men, women, children (some born along the way), and more than 1000 head of horses, mules and cattle. Crossing into California and toward the Pacific, the party went north to establish a new settlement at San Francisco. “Vayan Subiendo!” was the rallying cry.

Spain had been hoping for a good overland route to California. All they needed was to secure the crossing of the Colorado River at Yuma. Garces, along with a number of other priests, many soldiers and settlers, set about establishing missions on both sides of the Colorado.

While development at Yuma was underway, Garces wandered north up the Colorado then east into the lands of the Hualapai, the Havasupai and the Hopi. He was at Hopi on July 4, 1776, an insignificant date in that part of America, except that he had arrived on July 2, and the Hopi gave him two days to get off their mesa. He was the first priest to show up on Hopi lands since they killed his predecessors in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Seeing no chance of making Christians of the Hopi, he expressed his affection for them and headed back to Yuma.

Relations between the Spaniards and the Yumas were not going well. An uneasy peace prevailed for several years. The Spaniards promised gifts and supplies. But, more often than not, the Spaniards did not have enough for themselves and severely taxed the natives’ food supplies and patience. The Spaniards took over the best farmlands and abused, ridiculed and mistreated the natives. By 1781, the Yumas had had enough. An uprising in July drove the Spaniards from Yuma permanently. Natives destroyed the missions on both sides of the river and killed most of the men and all of the priests, Garces last of all.

De Anza’s 1775 - 1776 party was the first and only large group of settlers to go overland from Mexico to California. The ouster of the Spaniards in 1781 effectively closed the river crossing at Yuma for forty years.

A year or so before Garces was martyred, he wrote: “We have failed. It is not because we haven’t tried. It is because we have not understood.”

As our story moves into the early 1800s, the mission at Tumacacori and the settlement at Tubac are hanging on, San Xavier del Bac is growing into one of the most beautiful churches in all Christendom, and the presidio at Tucson is thriving. Any other Spanish influence in Arizona is gone.

Next time: 1821 — the end of Spanish rule.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at www.sharlothallmuseum.org/library-archives/days-past. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 14, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or to request assistance with photo requests.