By Dave Lewis

Previously: Spanish explorers first set foot in Arizona in 1539. They saw the land and major rivers, encountered numerous native tribes, and moved on. For the next 150 years, with a few exceptions, Spaniards made no attempt to remain in Arizona.

The exceptions: In 1629, Spanish missionaries from settlements along the Rio Grande came into the Hopi lands and established missions which were occupied intermittently for the next 50 years. At Hopi and throughout New Mexico, Spanish soldiers and priests virtually enslaved native people even as they worked to convert them to Christianity. In 1680, a rebellion was organized at Taos, and in a remarkably well-coordinated uprising on a single day in August, natives in several dozen far-flung pueblos and villages rebelled. Four hundred Spaniards were killed, including most of the priests; several thousand settlers were routed and chased down the Rio Grande toward Mexico. The few Spanish missions at Hopi were destroyed. Once again, Arizona belonged to the natives.

To the south, though, Spanish settlement was moving steadily northward, through Sonora into the valleys of the Santa Cruz and San Pedro and toward the Gila. The Spaniards called this province Pimeria Alta -- the upper lands of the Pima (or O’ohdam) Indians. Along the way, they established missions to minister to the natives and to secure Spain’s foothold. Most of the missions were south of the present-day U.S. - Mexico border; a handful were to the north. In the land that would become Arizona, Pimeria Alta was bordered on the east by the San Pedro River, on the north by the Gila River, and on the west by the Colorado.

A well-equipped Spanish mission had a priest and maybe a soldier or two, cattle and sheep, and fields of corn, wheat and other staple crops, with a goal of being self-sustaining, and more -- to provide food for the natives. A wise priest reasoned that a display of generosity, helping to fill the natives’ stomachs, might help reach their souls. Moreover, introduction of new crops and animals would improve the lives of the natives. Initially at least, the Pima were friendly, and found the missions to be useful refuges against Apache raids.

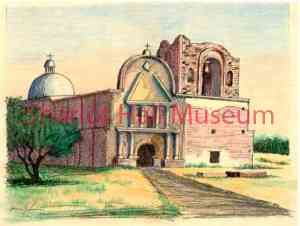

The natives revered a Spanish priest who became a principal figure in Pimeria Alta -- Father Eusebio Kino. In 1691 he established missions or “visitas” (sites visited occasionally by priests) in Arizona at Guevavi near Nogales, and at Tumacacori (“Too-ma-cah-cory”). In 1692 he added a mission at San Xavier del Bac. Houses of worship of sticks and brush gradually evolved into small adobe structures, and much later to graceful mission churches.

The natives revered a Spanish priest who became a principal figure in Pimeria Alta -- Father Eusebio Kino. In 1691 he established missions or “visitas” (sites visited occasionally by priests) in Arizona at Guevavi near Nogales, and at Tumacacori (“Too-ma-cah-cory”). In 1692 he added a mission at San Xavier del Bac. Houses of worship of sticks and brush gradually evolved into small adobe structures, and much later to graceful mission churches.

During Father Kino’s life (he died in 1711) and especially thereafter, native uprisings and Apache raids forced temporary abandonments of the missions. A major revolt by Pimas in 1751 took a toll, but, instead of leaving, the Spaniards established a much more substantial settlement -- a fort or “presidio” -- at Tubac in 1752. This time, the Spaniards garrisoned 50 soldiers along with the priests, and for the first time brought Spanish families -- settlers, women and children, into Pimeria Alta. Two hundred years after the Coronado Expedition, Spain had a permanent settlement in Arizona.

The role of the Church remained significant, but at the direction of the Spanish government, future settlements focused on maintaining a military presence and defending against Apache raids. In the early 1770s, Spain directed the establishment of a strategic line of presidios from Texas into Pimeria Alta. A Spanish officer thought the presidio at Tubac was inadequate for protection and decided to move the garrison north right into the heart of the area where the Apaches assembled for their attacks. The spot was named Tucson. In 1775 and 1776 a new, larger and stronger presidio was established there.

The role of the Church remained significant, but at the direction of the Spanish government, future settlements focused on maintaining a military presence and defending against Apache raids. In the early 1770s, Spain directed the establishment of a strategic line of presidios from Texas into Pimeria Alta. A Spanish officer thought the presidio at Tubac was inadequate for protection and decided to move the garrison north right into the heart of the area where the Apaches assembled for their attacks. The spot was named Tucson. In 1775 and 1776 a new, larger and stronger presidio was established there.

Tubac remained as a civilian settlement and mission. And, as American colonists on the East Coast were waging a war for independence from English rule, Spain had colonized New Mexico and now had a firm presence in Arizona. Spain next set her sights on California.

Before we leave this portion of the chronology, something interesting occurred not far south of today’s Nogales. In 1735 Spanish and Basque-speaking ranchers stumbled upon slabs of silver — one weighing some 2500 pounds. This area was in New Spain, in a province known as Pimeria Alta, but it was known to the local settlers as “Arizona.”

Next time: Vayan Subiendo! (“Everyone mount up”) for a trek to California.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at www.sharlothallmuseum.org/library-archives/days-past. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-277-2003, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information.