By Dave Lewis

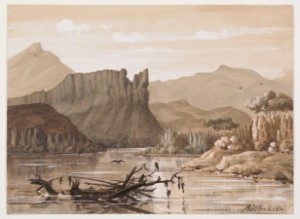

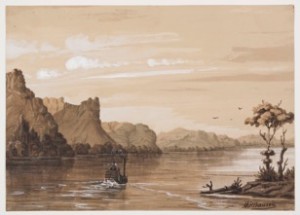

In January 1858, Lieutenant Joseph Ives set out from Yuma in the steamship Explorer to determine how far boats could go upriver on the mighty Colorado. While still within sight of amused spectators at Fort Yuma, his pilot ran the boat aground. This would happen many more times, usually to the delight of Indians gathered on the riverbank who knew the river and could predict the groundings.

Further detracting from the expedition’s glory, Yuma-based riverman George Alonzo Johnson beat Ives to the punch by running one of his boats upriver into Black Canyon several weeks before Ives. Johnson had offered Ives his services and the use of one of his boats. Ives rejected the offer; in a fit of competitive spirit, Johnson decided to do it first.

Despite this inauspicious beginning, Ives’s expedition was a crowning achievement of the Army’s splendid Corps of Topographical Engineers. Historian William H. Goetzmann acknowledged it as “one of the most remarkable American explorations of the nineteenth century.”

Despite this inauspicious beginning, Ives’s expedition was a crowning achievement of the Army’s splendid Corps of Topographical Engineers. Historian William H. Goetzmann acknowledged it as “one of the most remarkable American explorations of the nineteenth century.”

Going was very difficult. In one notable three-day period, they made only nine miles. Slow progress was frustrating, but was undoubtedly beneficial to the expedition’s scientific work, which they handled with extraordinary skill.

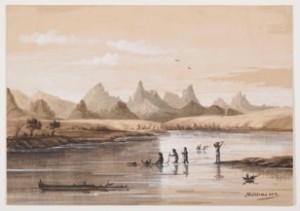

Among the achievements cited by historian Goetzmann was the expedition’s contact and generally friendly relations with largely unknown Indian tribes. The Indians were curious and often helpful as guides. Ives occasionally invited a few aboard the boat. Once, he proudly showed off his brass-rimmed compass. His visitors were fascinated but, observed Ives (who was never very self-effacing), once the Indians understood what the device was for, they thought he must not be very smart to need it to tell him which way he was going. In a charming aside, Ives recounted with some pride that he made a speech to a group of Indians without once mentioning “the Great White Father in Washington.”

Churning upriver, they passed the mouth of the Bill Williams River, which Ives had followed a few years earlier as an assistant to Lieutenant Amiel Whipple. Further on, near the Needles, they passed the spots where Capt. Lorenzo Sitgreaves came overland to the Colorado and where Lieutenant Edward Beale and his camels recently crossed. Those explorations were looking for potential railroad routes; Ives wanted to see if the river could become a highway.

Churning upriver, they passed the mouth of the Bill Williams River, which Ives had followed a few years earlier as an assistant to Lieutenant Amiel Whipple. Further on, near the Needles, they passed the spots where Capt. Lorenzo Sitgreaves came overland to the Colorado and where Lieutenant Edward Beale and his camels recently crossed. Those explorations were looking for potential railroad routes; Ives wanted to see if the river could become a highway.

Ives pressed the ungainly Explorer up several rapids, eventually entering Black Canyon not far from today’s Hoover Dam before striking one last rock and declaring that spot to be the head of navigation. Ives sent the Explorer back to Yuma while he and part of his crew rowed a skiff further upriver as far as Las Vegas Wash. They determined that the Mormon Road into Utah was not far to the west, and that the Virgin River was close by. Either of these would provide a route into Utah if the Army needed to move against the independence-minded Mormon settlers.

Ives and his men floated back down to the area of the Needles and then went east overland looking for additional access points to the Colorado. They found one at Diamond Creek, which they were able to follow down to the Colorado, becoming the first explorers to enter the Grand Canyon at river level. They were awestruck, but never at a loss for words.

Ives and his men floated back down to the area of the Needles and then went east overland looking for additional access points to the Colorado. They found one at Diamond Creek, which they were able to follow down to the Colorado, becoming the first explorers to enter the Grand Canyon at river level. They were awestruck, but never at a loss for words.

The expedition’s geologist, John Strong Newberry, looked at the canyons, the river, and the surrounding plateau country and drew the correct conclusion on the first try: it was flowing water, over countless eons, that had carved this country.

Ives had a different reaction to the area: it is “altogether valueless,” he wrote. Our next installment will explain that it was not necessarily meant as an insult.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at https://sharlothallmuseum.org/articles/days-past-articles.l. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.