By Dave Lewis

1857: The land that would become Arizona was still part of New Mexico Territory, but the name “Arizona” was gaining popularity among citizens around Tucson. Tucson, Tubac, and Yuma were the only non-native settlements in Arizona and knowledge of the region was growing slowly. Spaniards had been here since the 1500s. Mountain men and prospectors had crossed Arizona; Army expeditions had traversed Arizona along the Gila River and along the Mormon Trail south of the Gila. Lorenzo Sitgreaves, Amiel Whipple, and Edward Beale had surveyed possible wagon and railroad routes. There was even regular river boat activity on the lower Colorado, between Yuma to the Sea of Cortez.

Unknown was the course and character of the Colorado upriver from Yuma. Spaniards Coronado, Cardenas and Alarcon failed to unlock the river’s mystery more than 300 years earlier. In 1857, with westward movement and settlement increasing, the government was anxious to improve its understanding of the river and its canyons. The Army’s Corps of Topographical Engineers was given the assignment, with Lt. Joseph Christmas Ives in command.

Ives, educated at Yale and West Point, was a sensible choice for the plum assignment. He also happened to be related by marriage to Secretary of War John Floyd. His mission was to explore the Colorado upstream from Yuma to determine how far the river was navigable; to map the area; to conduct a hydrographic survey; to create a record of the terrain, the natives and natural history of the area; and to continue overland to map “the vicinity of the river as high up as may be practicable,” all in the winter months when the river’s flow was lowest -- less current to fight against, but shallower water with more exposed rocks and shoals.

Given a budget of about $40,000, a free hand to decide how to proceed and authority to recruit the necessary staff, Ives began preparations in the summer of 1857. His wisest decisions were in selecting specialists for the trip: John Strong Newberry, the country’s preeminent geologist; experienced cartographer and sketch-maker Frederick von Egloffstein; and veteran artist and natural historian Heinrich Balduin Möllhausen.

More dubious was his choice of a boat to run up the river. For some years, “Captain” George Alonzo Johnson had been running hundred-foot-long, shallow draft riverboats between the Sea of Cortez and Yuma, hauling passengers and supplies for the Army. If the government would sponsor his efforts, he was perfectly willing to try running upriver from Yuma in support of Ives’s mission. He offered the use of one of his boats for $3,500 a month. To Johnson’s considerable irritation, Ives declined. Cost was certainly a factor, but it is also likely that the ambitious Ives was unwilling to share credit for what was sure to be a heroic endeavor.

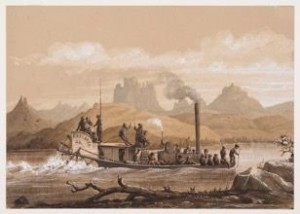

Ives contracted in Philadelphia for the construction of a special riverboat. His boat, the Explorer, was constructed, disassembled and shipped around to the Pacific Ocean and up to the head of the Sea of Cortez, where it was reassembled and launched. The Explorer was a fifty-four-foot-long stern-wheeler, heavy, with steel plates on the bottom, and weighed down even more with a large wood-burning steam engine, supplies, equipment and a crew of twenty-four. One critic suggested the craft had the seaworthiness of a wheelbarrow.

Ives contracted in Philadelphia for the construction of a special riverboat. His boat, the Explorer, was constructed, disassembled and shipped around to the Pacific Ocean and up to the head of the Sea of Cortez, where it was reassembled and launched. The Explorer was a fifty-four-foot-long stern-wheeler, heavy, with steel plates on the bottom, and weighed down even more with a large wood-burning steam engine, supplies, equipment and a crew of twenty-four. One critic suggested the craft had the seaworthiness of a wheelbarrow.

In January of 1858, the Ives Expedition began its slow churn up the river. The mission took on an increased sense of urgency as friction developed between President James Buchanan and Mormon leader Brigham Young regarding the President’s intention to exercise federal control over Utah, contrary to Young’s wish for independence and freedom to appoint his own chosen leaders. With the looming prospect of armed conflict between U. S. forces and the formidable Mormons, Ives was instructed to hurry and determine if the Colorado could be used to move troops into position to confront Young.

Up next: Ives draws an often-maligned and misunderstood conclusion about Arizona’s canyon lands.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at https://sharlothallmuseum.org/articles/days-past-articles.l. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.