By Dave Lewis

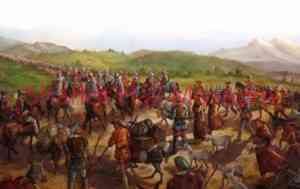

The people of Hawikuh laid down a line of sacred corn meal and asked the strange men riding strange animals not to cross. The Spaniards crossed and the battle was on. Zuni bows and arrows were no match for armored men on horseback with swords and lances. The proud but half-starved Spaniards swept into the village and feasted on the provisions the natives were laying by in the summer of 1540.

Thus began the first substantive contact between European explorers and natives of the Southwest. A year earlier, Fray Marcos de Niza with a few companions had approached Zuni. He saw a striking multi-story pueblo shining in the sun; he heard some rumors of wealthy cities; and his imagination took hold. By the time he got back to Mexico he was telling a tale of great cities of gold just waiting to be plundered, for glory of God and king, not to mention for the chance for brave men to line their pockets.

Thus began the first substantive contact between European explorers and natives of the Southwest. A year earlier, Fray Marcos de Niza with a few companions had approached Zuni. He saw a striking multi-story pueblo shining in the sun; he heard some rumors of wealthy cities; and his imagination took hold. By the time he got back to Mexico he was telling a tale of great cities of gold just waiting to be plundered, for glory of God and king, not to mention for the chance for brave men to line their pockets.

The honor of leading a great expedition to the north was granted to Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, a wealthy 37-year-old friend of Spanish Viceroy Mendoza. Coronado organized his expedition at Compostela on the west coast of Mexico and set out in February 1540. There were two-hundred twenty-five young caballeros, many from wealth and privilege, eager to go on what must have seemed like a holiday. Dozens of foot soldiers followed, along with a thousand Aztec allies, servants and slaves. Sheep and cattle were herded along as a food supply that was to run out much too quickly. And, of course, there was Fray Marcos to provide inspiration.

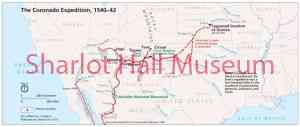

Several months and hundreds of hard miles later, marching north by east, they entered what is now Arizona -- most likely in the valley of the San Pedro River just below modern day Sierra Vista. “Most likely” because there is no absolute certainty of the route Coronado followed. No hard archaeological evidence has been found to prove their route through Arizona, but the Spaniards were keen observers of the terrain and the plants and animals, and they were prolific writers who kept meticulous records of their travels. Reasonable reconstructions of their route are drawn from these sources.

Even as the party approached the land now known as Arizona excitement had begun to fade. Accidents claimed life and limb; hunger, thirst and heat sapped enthusiasm; and a serious miscalculation of geography eliminated any chance of reaching Captain Alarcon’s ships which had sailed with fresh supplies up to the mouth of the Colorado River -- much further to the west than had been imagined.

Nonetheless, anticipating great riches to be found, the expedition trudged on. Their likely route took them along the San Pedro, over mountains and onto the Mogollon Rim, then northeast to the modern-day Arizona-New Mexico border toward the Zuni village of Hawikuh. The going had been slow; it was July when they arrived.

Nonetheless, anticipating great riches to be found, the expedition trudged on. Their likely route took them along the San Pedro, over mountains and onto the Mogollon Rim, then northeast to the modern-day Arizona-New Mexico border toward the Zuni village of Hawikuh. The going had been slow; it was July when they arrived.

The Zuni were not happy to see 1300 men, uninvited, showing up for dinner. Moreover, they were certainly unhappy with the attitude of the newcomers. The Spaniards read a long document, called The Requerimiento, to the uncomprehending natives they encountered. The Requerimiento ordered the natives to surrender in the name of God and the king. It set forth rules of behavior and established Spain’s dominion over the new lands and conquered people. It ended with the following:

“If you do not do what I ask, with the help of God, I will attack you mightily . . . I will make war against you everywhere and in every way I can. And I will subject you to the yoke and obedience of the Church and His Majesty. I will take your wives and children and I will make them slaves . . . I will take your property. I will do all the harm to you that I can.” If this happens, they added, it will be your fault, not ours.

A Spanish scribe penned this remarkable bit of understatement after finally succeeding in explaining the new rules to the inhabitants of one pueblo: “They were not familiar with His Majesty (King Philip II), nor did they wish to be his subjects.”

A Spanish scribe penned this remarkable bit of understatement after finally succeeding in explaining the new rules to the inhabitants of one pueblo: “They were not familiar with His Majesty (King Philip II), nor did they wish to be his subjects.”

Back to the story: After that initial skirmish, the Zuni determined to pacify the strangers with food and gifts, and to hurry them on their way. It was obvious to the Spaniards that Zuni was not a wealthy city. The Zuni assured them, however, that if they would just keep going they would find their great cities of gold.

In Part Three of our story, to be published on April 22, we continue our story of the Coronado Expedition. Garcia Lopez de Cardenas visits the Grand Canyon. He does not send a postcard home.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at www.sharlothallmuseum.org/library-archives/days-past. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles to dayspastshmcourier@gmail.com. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-277-2003, or via email at dayspastshmcourier@gmail.com for information.