By Barbara Patton

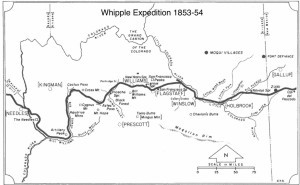

December 19, 1853, found the Whipple expedition encamped on the Little Colorado River. The next day, the team left the river, heading west toward the San Francisco Mountains where Whipple and a small exploratory team had found Leroux Springs. After several days traveling through deep snow, the expedition stopped at caves once inhabited by natives where they decided to remain through Christmas.

On Christmas Eve, the camp was in merry spirits. Whipple recorded, “Tall isolated pines surrounding the camp were set on fire. The flames leaped to the treetops, and then dying away, sent up innumerable brilliant sparks.”

On Christmas Eve, the camp was in merry spirits. Whipple recorded, “Tall isolated pines surrounding the camp were set on fire. The flames leaped to the treetops, and then dying away, sent up innumerable brilliant sparks.”

Two days after Christmas, Whipple led the group to Leroux Springs, where he had to make a major decision. Guides Leroux and Savedra both recommended turning northwest in the direction the Sitgreaves expedition had taken. However, Whipple was determined to follow the 35th parallel and find the Williams Fork River which Sitgreaves said flowed to the Colorado River.

The problem was that Sitgreaves had mistaken the headwaters of the Verde River as the source of the Williams Fork River, and he had miscalculated the latitude of the mouth of Williams Fork. It joined the Colorado River sixty miles south of the 35th parallel.

As a result, when Whipple led his men southwest, he was using inaccurate information. The route he followed took them first west past Bill Williams Mountain to the present-day Seligman area, then into a valley he named Chino. They explored another valley to the west looking for the elusive Williams Fork, but all rivers seemed to turn south.

By this time, Whipple was annoyed with his guides, who were of no use. Back in Chino Valley, he decided to head southwest toward a large mountain. Reaching Mount Hope, they found a pass which Whipple called Aztec Pass.

After crossing the pass, they found only more mountains. Whipple explored some treacherous terrain to the northwest with no luck. Finally, on January 29, two natives approached the camp. When Whipple asked them about the distance to the Colorado River, they told him it was a three-day journey directly west.

After crossing the pass, they found only more mountains. Whipple explored some treacherous terrain to the northwest with no luck. Finally, on January 29, two natives approached the camp. When Whipple asked them about the distance to the Colorado River, they told him it was a three-day journey directly west.

Whipple decided not to go directly west where he saw more mountains and instead led the group to the northwest through a pass in the Cottonwood Mountains. From there, he explored south and found a large stream he called Big Sandy. In reality, this was the sought-after Williams Fork.

The valley was beautiful, and the stream repeatedly disappeared beneath sand before bubbling back up further downstream. Although the valley was lush with plenty of game, the soft sand, rough terrain and dense chaparral made it difficult for the mule teams. And strangely, the mules seemed to be weak from hunger, even though they were camping in grassy areas.

With the increase of willows along the river, travel was more difficult, and the mules grew weaker. The decision was made to abandon most of the wagons. Ill himself, Whipple was despondent; however, a few days later he finally solved the mule problem. The sentries guarding the animals at night were keeping them penned too tightly, not letting them roam and feed. Once the mules were allowed to eat their fill of grass, they regained their strength.

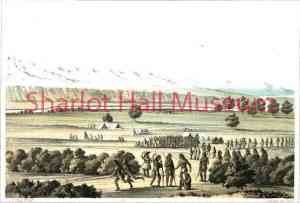

A few days later, the expedition reached the Colorado River. There they traded with local natives for food. They then traveled northward to find a suitable place to cross the river. Near present-day Needles, California, natives helped them ford their supplies using a rubber pontoon with a cart strapped to it and a system of ropes. The mules swam.

A few days later, the expedition reached the Colorado River. There they traded with local natives for food. They then traveled northward to find a suitable place to cross the river. Near present-day Needles, California, natives helped them ford their supplies using a rubber pontoon with a cart strapped to it and a system of ropes. The mules swam.

Leaving the river, they made a quick trip across Southern California and arrived in Los Angeles on March 2, 1854. Whipple had successfully surveyed and mapped a route along the 35th parallel which would guide later road builders and settlers.

His exploratory mission was a success; however, in 1863 at the Battle of Chancellorsville, General A.W. Whipple was shot. He died three days later in Washington D.C.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at https://sharlothallmuseum.org/articles/days-past-articles.l. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.