By Bob Harner

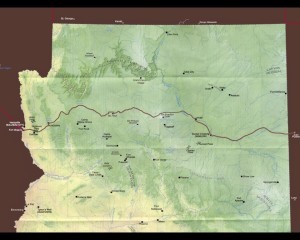

By the time the Sitgreaves expedition left Zuni, they knew Simpson’s report about a new way west was incorrect. Leroux, their guide, indicated the Zuni River did not flow into the Colorado, but into the Little Colorado River instead. Leroux proposed an alternative route, following the Zuni to the Little Colorado, following that river to the Bill Williams Fork via the San Francisco Mountains, then to the Colorado and the Old Spanish Trail. Leroux was incorrect about where those rivers went, but he had never been west of present-day Winslow.

By the time the Sitgreaves expedition left Zuni, they knew Simpson’s report about a new way west was incorrect. Leroux, their guide, indicated the Zuni River did not flow into the Colorado, but into the Little Colorado River instead. Leroux proposed an alternative route, following the Zuni to the Little Colorado, following that river to the Bill Williams Fork via the San Francisco Mountains, then to the Colorado and the Old Spanish Trail. Leroux was incorrect about where those rivers went, but he had never been west of present-day Winslow.

The going was slow, seldom more than 10 or 15 miles a day. Moving pack animals up and down arroyos and river canyons proved difficult. At times, the men used ropes to haul mules up cliffsides. Although they frequently found signs of game, they had little luck killing anything to supplement their food supplies.

Early in October, about five miles from present-day Holbrook, they had their first glimpse of the San Francisco Mountains, which Richard Kern described as “looming up nearly due west and so far off it seemed like a dream.”

Sitgreaves is occasionally credited with discovering the seasonal Grand Falls, but they were already familiar to his Mexican muleteers and to Kern. Sitgreaves was, however, the first to write a published description of the Wupatki Ruins, and Kern illustrated them for the official government report.

Leroux next incorrectly believed that a seasonal stream they found was the Bill Williams Fork, which could be followed to the Colorado. It was what is now called Hell Canyon. The Bill Williams Fork was more than 50 miles southwest of their location. Leroux also thought the Colorado was less than 100 miles away. He was very wrong. Apparently losing confidence in his guide, Sitgreaves only followed the wrong stream for a day before setting off overland, soon following the route of today’s Interstate 40.

Warned he might encounter the Grand Canyon if he strayed too far north, Sitgreaves took his now-exhausted expedition across the San Francisco Mountains. Food began to run low and hunting was still largely unsuccessful. Mules began to tire and die, becoming a supplemental food source.

Although the party traded occasionally with natives along the way, they also came under attack. In one skirmish, Leroux received arrow wounds in both the head and wrist, the arrow in the wrist reaching the bone, disabling him for the rest of the trip.

Early in November, they came within sight of the Colorado River far below. Campfire smoke indicated a large population of natives along the river. Sitgreaves reported the sight of the river “brought a spontaneous cheer from the men who believed that this was to be the end of their privations….” Unfortunately, that was not the case.

Occasionally under attack as they traveled along the Colorado, Woodhouse took an arrow in the leg, and a soldier who lagged behind the others was clubbed to death. Mules that were dying daily of starvation became their primary food source. Without enough pack animals, they began abandoning any equipment that wasn’t necessary for survival or defense.

Finally, on November 30, they arrived at Camp Yuma near the mouth of the river. This wasn’t Fort Yuma, which had been abandoned, but a small group of soldiers left behind to help travelers. The soldiers were able to feed the exhausted and starving expedition, but soon concluded they could no longer be supplied at their location and decided to abandon the camp and travel with the expedition to San Diego. Two months after starting, the expedition had two dead, two wounded and almost no mules. They had traveled 658 miles from Zuni to Camp Yuma, the official end of the expedition, plus additional miles to San Diego.

Sitgreaves seemed unhappy with the results of his travels. His report to Congress was only 17 pages, describing the area as: “barren and without general interest” and “the most perfect picture of desolation I have ever beheld….”

Although Sitgreaves didn’t find the western route he hoped for, he produced valuable maps (drawn by Kern from Sitgreaves’ observations), and his route across the northern part of the future Arizona would later become a railroad route and eventually Route 66 and Interstate 40.

The most important results of the expedition, however, were Kern’s illustrations for the official report, giving many Americans their first look at native lifestyles and ceremonies, as well as the vast and varied landscape of the unexplored territory. Richard Kern is the subject of the next article in our series.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at https://sharlothallmuseum.org/articles/days-past-articles.l. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.