By Bob Harner

After the Mexican-American War, converging events made finding a southern route to the West increasingly more urgent. The 1849 California Gold Rush launched a flood of westbound travelers, most following existing northern trails from St. Louis. Winter snows made these trails dangerous or impassable. Adding to the pressure was the Army’s need to supply new western posts created following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The Army Corps of Topographical Engineers was tasked with answering these needs.

The best way west seemed clear. Maps created by Major William Hemsley Emory placed Santa Fe at 35 degrees, 41 minutes north latitude, while California maps showed Los Angeles near 34 degrees north. It seemed a trail along the 35th parallel from the Rio Grande could reach the Pacific in half the time of northern trails. The Grand Canyon would have to be avoided, but its exact location and size had not been mapped.

In spring of 1849, Lieutenant James Hervey Simpson was tasked with finding a western route from Albuquerque. Arriving in Santa Fe, however, he was re-assigned to an expedition under Colonel John M. Washington against a group of hostile natives in Canyon de Chelly. On the way, just east of the Zuni Pueblo, Simpson noticed a stream flowing to the south. He was informed by the expedition’s guide that the stream flowed southwest into the Colorado and the route along the way was easily passable. Neither was true.

In spring of 1849, Lieutenant James Hervey Simpson was tasked with finding a western route from Albuquerque. Arriving in Santa Fe, however, he was re-assigned to an expedition under Colonel John M. Washington against a group of hostile natives in Canyon de Chelly. On the way, just east of the Zuni Pueblo, Simpson noticed a stream flowing to the south. He was informed by the expedition’s guide that the stream flowed southwest into the Colorado and the route along the way was easily passable. Neither was true.

Returning to Santa Fe, Simpson wrote a report repeating the guide’s assertions, concluding a route westward to the Pacific from that river juncture must exist and that it could “shorten the distance to San Francisco, at least from three to four hundred miles, if not more.” The stage was set for the Sitgreaves expedition.

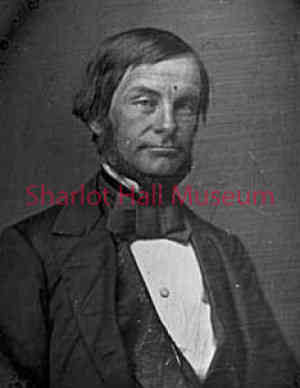

Lorenzo Sitgreaves graduated from the military academy in 1832, but soon resigned from the Army to become a civil engineer when officer pay proved inadequate. An economic depression in 1837, the creation of the Corps of Topographical Engineers and an increase in officer pay brought him back into military service.

After serving with distinction in the Mexican-American War, Sitgreaves completed several surveying assignments. Following Simpson’s report of a possible southern route to the West, Captain Sitgreaves received an order in November of 1850 from the head of the Topographical Corps, Colonel John James Abert, stating: “The River Zuni is represented on good authority to empty into the Colorado....pursue the Zuni to its junction with the Colorado....[and] pursue the Colorado to its junction with the Gulf of California….”

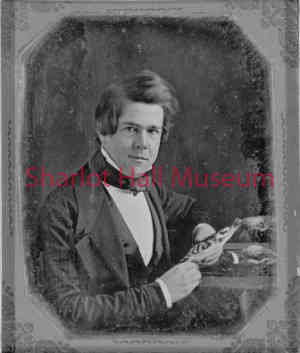

Joining Sitgreaves was Lieutenant John G. Parke (another topographical engineer), Dr. S. W. Woodhouse (naturalist and physician), Richard Kern (draughtsman and artist) and Antoine Leroux (guide). Sitgreaves had worked previously with Woodhouse and Kern. Because overland winter travel to Santa Fe was hazardous, Sitgreaves and Woodhouse sailed from New York to New Orleans via Havana, Cuba, arriving in New Orleans in January, 1851. Traveling overland and by river, they didn’t arrive in El Paso until June 24 and in Santa Fe on July 15, where they joined Kern, Parke and Leroux. Finally, on August 13, they left Santa Fe for the Zuni Pueblo to assemble the rest of the expedition.

Joining Sitgreaves was Lieutenant John G. Parke (another topographical engineer), Dr. S. W. Woodhouse (naturalist and physician), Richard Kern (draughtsman and artist) and Antoine Leroux (guide). Sitgreaves had worked previously with Woodhouse and Kern. Because overland winter travel to Santa Fe was hazardous, Sitgreaves and Woodhouse sailed from New York to New Orleans via Havana, Cuba, arriving in New Orleans in January, 1851. Traveling overland and by river, they didn’t arrive in El Paso until June 24 and in Santa Fe on July 15, where they joined Kern, Parke and Leroux. Finally, on August 13, they left Santa Fe for the Zuni Pueblo to assemble the rest of the expedition.

Before the expedition got started, however, Woodhouse was bitten by a rattlesnake he tried to capture. In the medical section of the official expedition report that Sitgreaves presented to Congress, Woodhouse described his physical reactions to the bite in detail. He also described the attempted cure (recommended by Kern) of getting drunk, downing half a pint of whiskey and a quart of brandy (while soaking his finger in ammonia) as quickly as possible, reporting that he remained drunk for four to five hours and that, unsurprisingly, “During this state I vomited freely.” He recovered sufficiently to travel but kept his arm in a sling until mid-November. In a published journal of his travels, he refers to “this miserable country where everything appears to be your enemy and is armed with a thorn or a poisonous sting.”

On September 24, the expedition departed, with over seven tons of baggage carried by 80 mules, 47 sheep (the Army estimated one sheep could feed seven men for one day), 56 days of food supplies, five American and 10 Mexican muleteers and 30 soldiers.

In next week’s article, the Sitgreaves Expedition gets underway.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at https://sharlothallmuseum.org/articles/days-past-articles.l. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.