By Dave Lewis

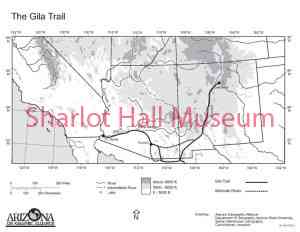

Last week: The United States was at war with Mexico. General Stephen Kearny took the Mexican capital at Santa Fe and headed across Arizona to take California. Kit Carson led the way. Carson had been in California with John C. Fremont a month earlier and told Kearny that Fremont had already taken California. Nonetheless, California was Kearny’s responsibility and he was bound to go. By mid-October they entered Arizona near the present-day town of Clifton and began struggling down the Gila River.

The route along the Gila might have been the most direct way to California but it was extraordinarily difficult. The physician on the trek wrote colorful accounts of the difficult going:

“Oct. 21, 1846: . . . a long and fatiguing day. When we left camp this morning we had two difficulties presented to us – the one a most steep and rugged mountain, the other a canyon of the river, we took the latter as the lesser evil, followed down the Gila some five or six miles and finally turned the steepest part of the mountain. In following the course of the river, we were obliged to cross it every half mile or so, the mountain jutting down to the very edge of the stream, making a very picturesque affair of it – but damn bad roads – the fact is we have so much of the grand & sublime scenery that I am tired of it.”

“Oct. 21, 1846: . . . a long and fatiguing day. When we left camp this morning we had two difficulties presented to us – the one a most steep and rugged mountain, the other a canyon of the river, we took the latter as the lesser evil, followed down the Gila some five or six miles and finally turned the steepest part of the mountain. In following the course of the river, we were obliged to cross it every half mile or so, the mountain jutting down to the very edge of the stream, making a very picturesque affair of it – but damn bad roads – the fact is we have so much of the grand & sublime scenery that I am tired of it.”

They toiled this way for several weeks before the river left the mountains and offered slightly easier passage across the desert.

Historian Edwin Corle speculates on Kearny’s mood “He could visualize Commodore Stockton and Colonel Fremont organizing and governing the prostrate Spanish California, and he knew it was his business to be there and to do it. There they were, the happy conquerors, and here he was, assigned to such a job, still battling his way down the blasted Gila River.”

As they passed sixty miles north of the Mexican garrison at Tucson they decided simply to ignore it. If the Mexicans knew they were there, they, also, chose not to engage. But an opportunity for battle would present itself soon enough.

As they passed sixty miles north of the Mexican garrison at Tucson they decided simply to ignore it. If the Mexicans knew they were there, they, also, chose not to engage. But an opportunity for battle would present itself soon enough.

They reached the Colorado River in late November. To their shock, letters taken from a captured Mexican messenger reported that Mexican forces had rallied and had re-taken San Diego, Santa Barbara and Los Angeles.

Kearny’s small and fatigued force hurried across the desert. On December 6th in the mountains east of San Diego they were attacked by Mexican cavalry; one third of Kearny’s men were killed. The remainder might have met the same fate but were saved by a detachment of Commodore Stockton’s men under Army Lieutenant Edward Beale. For the next month, the forces of Kearny, Stockton and Fremont skirmished with the Mexicans, and finally won California in January 1847.

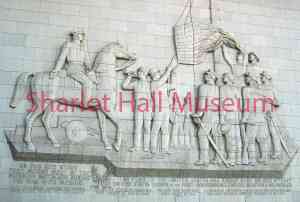

Meanwhile, a remarkable and heroic force of Americans known as the Mormon Battalion was headed west toward California under the command of Colonel Philip St. George Cooke. More than 300 Mormon men and the wives of a handful of officers formed a great wagon train. Their mission was to join the fighting against the Mexicans and, of equal importance, to blaze the first wagon road from Santa Fe to Southern California.

Their route was far more practical for wagon travel than Kearny’s torturous trail, but they still had to carve their way through rocks and hack through brush. The route followed the Rio Grande south, below the modern-day Mexican border, then northwest to the San Pedro River, north toward Tucson, northwest to the Gila and then west to the Yuma crossing. This route was hundreds of miles longer, but it avoided the rough mountains of eastern Arizona and the worst of the Apache domain.

Among the notable experiences of the Mormon Battalion were:

Arizona’s “Battle of Bull Run” (or run, the bulls are attacking!). As the wagon train came up into far southern Arizona, they entered an area where Apaches grazed wild cattle. Dozens of enraged bulls attacked, turning over wagons and goring mules. It was all the Mormons could do to defend themselves

The battalion entered Tucson prepared to fight for control of the town, but they met no resistance. For the first time, an American flag flew over Tucson.

By the time the Mormons reached California in late January 1847, the fighting was over. Historian Jay Wagoner summarizes the end of the war:

By the time the Mormons reached California in late January 1847, the fighting was over. Historian Jay Wagoner summarizes the end of the war:

“None of the expeditions into Arizona affected the outcome of the Mexican War. Victory was achieved by the army of General Winfield Scott, who entered Mexico City on September 14, 1847. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 formally established peace.”

Next time: The results of the Mexican-American War – Arizona becomes New Mexico.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at https://sharlothallmuseum.org/articles/days-past-articles.l. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.