By Dave Lewis

Thus far in our series of occasional articles, we have discussed the Spanish entradas, missions and settlements south of the Gila River, Mexico’s independence from Spain, and a few of the mountain men who crossed this land -- all against the backdrop of the area’s challenging terrain and the lives and cultures of Natives who predated the arrival of Europeans by 10,000 years. By the 1840s, Mexico had population and governmental centers at Santa Fe and several places in Southern California; the small settlements at Tubac and Tucson were the only Mexican presence in what would become Arizona. The rest of Arizona was left to the Indians.

That would begin to change in May 1846, when President James K. Polk, citing unprovoked Mexican aggression along the Texas border, asked Congress to declare war on Mexico. Polk had tried unsuccessfully to persuade Mexico to sell the United States a huge swath of land from Texas to the Pacific. Now he was prepared to take it by force. War with Mexico proceeded on several fronts -- none of them in Arizona.

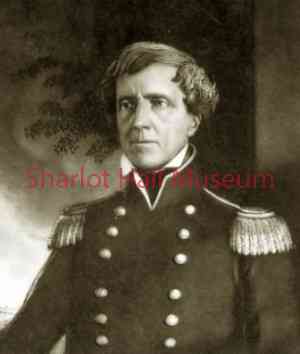

To our east, Colonel Stephen Watts Kearny marched his Army of the West into Santa Fe in August 1846 and took the town without firing a shot. So amiable was his takeover that the Mexicans fired a salute to the raising of the American flag, and Kearny hosted a ball for the Mexican officers and prominent residents. Historian Jay Wagoner noted:

To our east, Colonel Stephen Watts Kearny marched his Army of the West into Santa Fe in August 1846 and took the town without firing a shot. So amiable was his takeover that the Mexicans fired a salute to the raising of the American flag, and Kearny hosted a ball for the Mexican officers and prominent residents. Historian Jay Wagoner noted:

“On September 22, he proclaimed an American civil government in Santa Fe with a code of laws, a bill of rights, and a governor. Most of Arizona was included in the province and for the first time the political institutions of the United States were applied to this area, though there were probably no Americans in Arizona to appreciate the benefits. . .”

Beyond Santa Fe, Kearny’s mission was to press westward and take control of California. In late September, he set off with 300 dragoons (cavalry) and a couple of pieces of light artillery. These howitzers were mounted on the first wheels ever to roll onto Arizona soil, and they were nothing but an aggravation as the Army struggled to move them over the rough ground.

Meanwhile, in California, Commodore Robert Stockton and Lt. Col. John C. Fremont (later to reside in Prescott as the fifth governor of Arizona Territory) believed they had achieved an equally successful conquest of Mexican forces there. Fremont had marched south from San Francisco to Los Angeles in September 1846 with a small army and had encountered virtually no Mexican resistance.

So confident was Fremont in his victory that he sent his aide, Kit Carson, east with dispatches for Washington proclaiming that California was under United States control. Carson crossed southern Arizona and had reached the Rio Grande south of Albuquerque when he met Kearny (by now brigadier general). Carson advised Kearny of the victory in California and of his assignment to deliver the news to Washington.

General Kearny, eager to get to California, decided to take advantage of Carson’s unique knowledge of the terrain and directed him to lead the way. Kearny trusted Fremont’s report that California had been taken. He sent most of his army back to Santa Fe along with Fremont’s messages to be forwarded to Washington and then hurried west.

General Kearny, eager to get to California, decided to take advantage of Carson’s unique knowledge of the terrain and directed him to lead the way. Kearny trusted Fremont’s report that California had been taken. He sent most of his army back to Santa Fe along with Fremont’s messages to be forwarded to Washington and then hurried west.

Carson led Kearny’s smaller force over mountains in western New Mexico to the headwaters of the Gila River. Journals of Kearny’s officers describe the upper Gila:

“Some hundred yards before reaching the river the roar of its waters made us understand that we were to see something different from the Rio Grande. Its section where we struck it 4347 feet above the sea, was 50 feet wide and an average of two feet deep. Clear and swift, it came bouncing from the great mountains to the north . . . about 60 miles distant.”

They were delighted with the beauty of the river and the abundance of fine fish and quail. Their delight was short-lived. Scarcely a day later the mood began to change. The party’s physician wrote that the way along the riverside was “. . . quite level, but ye gods, the dust. I never suffered or saw men suffer more from any trifling annoyance in my life. We saw some geese, ducks and quail . . . No other game was seen, the fact is Carson says he never knew a party on the Gila that did not leave it starving, this I am fearful will be our case.”

The going only got worse. And Fremont’s reports of conquering Mexican forces in California proved to be premature. The story of the Mexican American war will continue next week.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at https://sharlothallmuseum.org/articles/days-past-articles.l. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.