By Murray Smolens

Old Bill Williams was in a quandary. It was November 1848; snow was early and deep in the mountains of the West. John C. Frémont, the famous “Pathfinder,” was determined to find a route for a transcontinental railroad through the Rockies. He had already been warned by eastbound travelers not to proceed, but the Pathfinder was stubborn. Unable to find old pal Kit Carson to lead or to persuade any other reliable guide to help, he ran into Old Bill in Pueblo (in present-day Colorado) who was recuperating from a clash with his old friends, the Utes, and their Apache allies. Frémont wouldn’t take no for an answer, double-dog-daring the 61-year-old mountain man into a decision that resulted in disaster.

Before he was “Old Bill,” William Sherley Williams was preacher, missionary, trapper, trader, and even a shopkeeper. He was born on January 3, 1787, in Rutherford County, North Carolina. His family moved to Missouri in 1794. Brought up by devout Protestants in a Catholic territory, he became a fire-and-brimstone preacher at seventeen. In contrast with his raggedy appearance and thick high-pitched drawl, he was literate, intelligent and fluent in several languages and Indian dialects.

Before he was “Old Bill,” William Sherley Williams was preacher, missionary, trapper, trader, and even a shopkeeper. He was born on January 3, 1787, in Rutherford County, North Carolina. His family moved to Missouri in 1794. Brought up by devout Protestants in a Catholic territory, he became a fire-and-brimstone preacher at seventeen. In contrast with his raggedy appearance and thick high-pitched drawl, he was literate, intelligent and fluent in several languages and Indian dialects.

He set off to “civilize” and Christianize neighboring Osage Indians but found their ways more to his taste and decided to live among them. He even took an Osage wife, Wind Blossom, whom he called Naomi. The Osage called him Pah-hah-soo-gee-ah (“Red-headed Shooter”) thanks to his flaming head of hair and remarkable accuracy with “Kicking Betsy,” his trusty rifle. His unorthodox “double-wobble” method of aiming led many unsuspecting folks to bet against him at the legendary mountain-man rendezvous over the years; Bill rarely lost these bets.

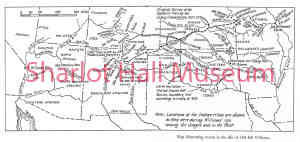

Bill had two daughters, Mary and Sarah, before Naomi tragically died around 1821. Bill was crushed. He stayed with the Osage for a few years, but his restless nature led him to leave his children to take a job as interpreter with US Army Major George C. Sibley in 1825 on an expedition from St. Louis to Santa Fe in an early effort to map a trade route from east to west. Bill spent the next several decades wandering the West, trapping and living off the land, usually alone or in small groups of fellow mountain men, including such legends as Thomas Fitzpatrick, Jim Bridger, Kit Carson and Joe Walker, a good friend from their encounters at rendezvous and joint explorations.

Bill had two daughters, Mary and Sarah, before Naomi tragically died around 1821. Bill was crushed. He stayed with the Osage for a few years, but his restless nature led him to leave his children to take a job as interpreter with US Army Major George C. Sibley in 1825 on an expedition from St. Louis to Santa Fe in an early effort to map a trade route from east to west. Bill spent the next several decades wandering the West, trapping and living off the land, usually alone or in small groups of fellow mountain men, including such legends as Thomas Fitzpatrick, Jim Bridger, Kit Carson and Joe Walker, a good friend from their encounters at rendezvous and joint explorations.

Bill developed keen survival skills in these years. He signed documents “Bill Williams, Master Trapper,” and no one disputed the title. He was a skilled horseman and master of the famous Green River knife, along with his deadeye shooting ability. He combined these with a tough, rugged physique and a preternatural ability to track man and beast, escaping certain death many times. But no one lives forever.

Now, in 1848, Old Bill, tired, worn and still weakened from the run-in with the Utes and Apaches, reacted to Frémont’s baiting tactics by exclaiming, “Dem’s fightin’ words!” But he didn’t fight; he joined.

He knew it was going to be an impossible journey, but he had done the impossible before, and he was never one to shirk a challenge. So, they set off into the mountains. The weather got worse, the snows continued to pile up by the foot, the winds howled relentlessly, the temperature dipped below zero, and supplies ran out. Frémont rejected Bill’s suggestion that they hew to a more southerly route, stripped him of his guide duties, and replaced him with Alexis Godey, a faithful Frémont friend but out of his element in this unfamiliar territory. Unable to hunt or forage, eleven of the 32 explorers died, but not Old Bill. Despite his age and infirmities, he made it to Taos, New Mexico, and recovered by late winter.

He knew it was going to be an impossible journey, but he had done the impossible before, and he was never one to shirk a challenge. So, they set off into the mountains. The weather got worse, the snows continued to pile up by the foot, the winds howled relentlessly, the temperature dipped below zero, and supplies ran out. Frémont rejected Bill’s suggestion that they hew to a more southerly route, stripped him of his guide duties, and replaced him with Alexis Godey, a faithful Frémont friend but out of his element in this unfamiliar territory. Unable to hunt or forage, eleven of the 32 explorers died, but not Old Bill. Despite his age and infirmities, he made it to Taos, New Mexico, and recovered by late winter.

When Frémont asked for volunteers to go back to the mountains to recover a cache of instruments and supplies left behind, there was Old Bill once again answering the call, along with Dr. Benjamin Kern, one of the surviving party members. On March 14, 1849, after finding and packing the supplies, Dr. Kern and Old Bill were surprised by a party of Utes and shot dead.

News of Old Bill’s demise spread rapidly and was greeted with widespread grief. Even the Utes, when they realized whom they had killed, gave him a chief’s burial, it is said.

Two years later, Dr. Kern’s brother Richard, and guide Antoine Leroux, traveling with the Sitgreaves Expedition in Northern Arizona, named a mountain and a river after Bill Williams. In 1876, cattle and sheep ranchers in Northern Arizona founded a town they called Williams, in honor of the old trapper who spent many a day crisscrossing the area’s idyllic woodlands.

Two years later, Dr. Kern’s brother Richard, and guide Antoine Leroux, traveling with the Sitgreaves Expedition in Northern Arizona, named a mountain and a river after Bill Williams. In 1876, cattle and sheep ranchers in Northern Arizona founded a town they called Williams, in honor of the old trapper who spent many a day crisscrossing the area’s idyllic woodlands.

A mountain, a tributary of the Colorado River, and a city are testaments to the lasting respect the man — also known as “Old Solitaire” — garnered throughout his colorful and adventurous life.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at https://sharlothallmuseum.org/articles/days-past-articles.l. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.