By Mick Woodcock

The aim of President Woodrow Wilson and most American citizens in 1916 was to avoid getting involved in what was perceived as another European war. There was no planning or preparation for America to go to war. When war was declared, however, there was an immediate flurry of activity in Washington, DC, to put the country on a wartime footing.

Waging war is expensive business. The estimated cost of World War I was $32 billion. The United States shouldered a disproportionate share of that with an estimated cost of $26.4 billion. America’s share in today’s dollars would be roughly $550 billion. This is only slightly less than the entire Department of Defense budget for fiscal year 2017. We know that today this is paid from individual and corporate income taxes, but what was going on in 1917?

The income tax as we know it was created by the 16th Amendment ratified February 3, 1913. This was not the first income tax however, as the Federal government had passed the Revenue Act of 1861 to help fund the Civil War. This was repealed in 1871 and the country went without an income tax until 1894 when Congress passed a flat rate income tax that the Supreme Court ruled was unconstitutional.

In 1916 the top tax rate on personal income was 15%. That all changed when Congress passed the War Revenue Act of 1917. With this the top tax rate on personal income jumped to 67%. For the average wage earner the rate went from 2% to 5%, more than doubling the amount of taxes owed.

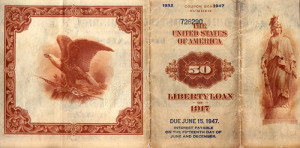

The second method used to raise revenue was to sell treasury war bonds. These were referred to as "Liberty Bonds." There were four bond issues during the war. The first was the Emergency Loan Act of April 14, 1917. That authorized the sale of $1.9 billion in bonds at 3.5% interest. These were not popular as the rate of interest offered was below other notes that could be purchased.

The second method used to raise revenue was to sell treasury war bonds. These were referred to as "Liberty Bonds." There were four bond issues during the war. The first was the Emergency Loan Act of April 14, 1917. That authorized the sale of $1.9 billion in bonds at 3.5% interest. These were not popular as the rate of interest offered was below other notes that could be purchased.

The government started an energetic campaign of advertising to boost the popularity of the bonds with the average person rather than major investors. This helped some, but a Second Liberty Loan initiated on October 1, 1917, offered $3.8 billion in bonds at a rate of only 3%, which did not help the cause.

The Third Liberty Loan came on April 5, 1918, with the aim of selling $4.1 billion in bonds at 4.15% interest. And the Fourth Liberty Loan offered $6.19 billion in bonds at 4.25 percent. The total sale from all of the bond drives amounted to about $17 billion. Although issued after the end of the war, on April 21, 1919, the Victory Liberty Loan was proclaimed as the last of the war loans. Offering $4.5 billion worth of bonds at 4.75%, it was the most lucrative of the five bond issues.

Repayment of the bonds became a problem for the United States Government as the Great Depression set in during the 1930s, but that is another story.

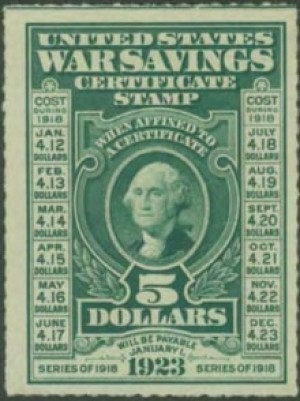

The final method to raise money for the war effort was through the sale of War Savings Stamps. These were sold in small denominations and were designed to get the entire population to financially support the war effort. Thrift stamps at 25 cents each were sold individually with the idea that collecting twenty of them would allow the purchaser to turn them in for a $5 War Savings Certificate stamp. Although these were popular with children and adults alike, their sale fell short of the $2 billion goal by $1.07 billion.

The final method to raise money for the war effort was through the sale of War Savings Stamps. These were sold in small denominations and were designed to get the entire population to financially support the war effort. Thrift stamps at 25 cents each were sold individually with the idea that collecting twenty of them would allow the purchaser to turn them in for a $5 War Savings Certificate stamp. Although these were popular with children and adults alike, their sale fell short of the $2 billion goal by $1.07 billion.

The citizens of Arizona and Yavapai County in particular were patriotic to the core. They met their goals in each of the four bond drives. The State also met its goal in the sale of War Savings Stamps with Yavapai County residents being the largest purchasers of stamps in Arizona.