By Jan MacKell

"The ancient card faces painted on the layout were doubtless faded and worn, but to my boyish eyes they glowed like a church's stained-glass window.... (Gaye) started drawing the cards one by one from the battered old silver box. As he drew, I could see his lips move and knew he was making bets for imaginary customers." So did Nugget (the main character in Conrad Richter's book "Tacey Cromwell") describe how his brother practiced to become a faro dealer in Bisbee during the late 1800s.

Faro was once much more popular than poker, so chosen because it was amazingly easy to play and odds for winning were the best of all gambling games. Nary a saloon in the West was without it between 1825 and 1915, with several well-known figures of the time making their riches by banking the game.

With origins in France during the early 1700s, "Pharaoh," as it was originally called, soon spread to the United States. In America, the name was shortened to faro, but was also known as "Bucking the Tiger" due to the picture of a Bengal tiger that often appeared on the back of American playing cards. The game was played with one deck and a faro board painted (or pasted) with 13 cards from Ace to King (usually the suit of spades) plus a square for betting on the high card. Players placed their bets in the form of chips on chosen card values, including the high card square.

The dealer then placed the deck into a "dealing box." The first card dealt was placed out of play. The rest of the game consisted of dealing the remaining 51 cards, one at a time, into two piles, placing one card on a "winner" pile and the next on a "loser" pile. Simply put, the pile on the left lost and the pile on the right won. The dealer settled all bets after each two cards were drawn. This allowed players to bet again before the next two cards were drawn. Players could also bet on whether the winning card was higher than the losing card. A player could also place a "Copper" (multi-sided chip) on any card to bet that it would appear in the losing pile. There were many ways to win - or lose - in this game.

The game got more interesting near the end as players bet on the cards that had not yet been played, thus increasing their odds of winning. The last three cards in the deck were reserved for "calling the turn." In this final bet, players could call the exact order in which the three cards might appear. The house paid 4 to 1 on these bets, but the odds of winning were purely chance.

Officially, three employees of the house ran the game: the dealer, who dealt the cards; the lookout, who made sure the game was square; and the case keeper, who used an abacus to track the cards as they were played. When three of the same number card had been played, the case keeper called out "cases!" When four of the same number card had been played, the abacus beads for that card were arranged so players knew the set had been played.

Because the game generally moved fast, it was very easy to cheat. Players could win via sleight-of-hand tricks while a seasoned dealer could manipulate the cards to favor the house. In time, even companies that produced legitimate gambling devices also made dealing boxes with a special button that could be pressed to release two cards instead of one! The house increased its odds this way but the game could still be won by one lucky guess of the final three cards. Arguments, fights and shootouts soon became a trademark of faro in the roughest of towns.

And so it was with Prescott. William Owen O'Neill's 17 years in Prescott were crowded with activity - probate judge, sheriff, mayor and editor. In his early 20s he became drawn to the excitement of card games on Whiskey Row, especially faro, and "bucked the tiger" (went against the odds) with such enthusiasm that he earned his nickname of "Buckey."

In the end, faro began losing its appeal during the early 1900s. Most veterans of the game could identify a crooked "dealing box" and card cheats. Gambling houses gradually moved on to games of chance that gave better odds to the house. Jim Finley, who dealt the game in Nevada for over three decades, in 2000 mourned the loss of the West's favorite card game, stating, "The casinos today aren't in gambling. They don't want a game you can win." Reno was the last holdout featuring faro amongst its table games until about 1985. In time, many folks simply forgot that faro was once the most popular card game in the West.

Its popularity has influenced our culture with many references to the game: Wyatt Earp and "Doc" Holliday both dealt faro in saloons of Tombstone; Casanova was known as a great faro player; numerous references were made in the radio drama "Gunsmoke"; in Tolstoy's "War and Peace," Nicholas Rostov lost 43,000 rubles to Dolokhov playing faro; the game is central to the plot of Pushkin's "The Queen of Spades"; in "Showboat," gambler Gaylord Ravenal specialized in the game of faro; and, along with many other links, the town of Faro, Yukon, was named after the game.

Jan MacKell, an author and historian, recently moved to Prescott and works at the Sharlot Hall Museum Store.

This and other Days Past articles available at sharlothallmuseum.org/library-archives/days-past. The public is encouraged to submit articles for Days Past consideration. Please contact Scott Anderson at Sharlot Hall Museum Archives at 445-3122 for information.

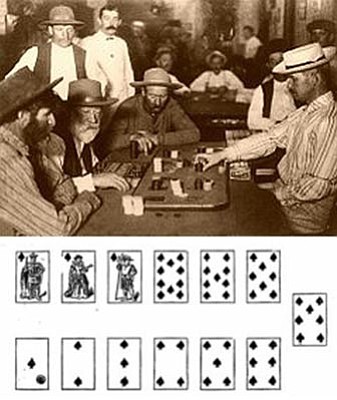

Courtesy photo

Nary a saloon in the West was without the card game of faro between 1825 and 1915, shown here in an Arizona saloon in 1895.