By Mick Woodcock

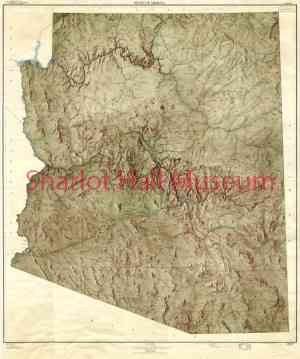

Arizona was nicknamed the “Baby State” for forty-seven years until Alaska’s statehood. Before that, she was a territory for forty-nine years. For the previous fifteen years, much of the area was part of the New Mexico Territory. From when it was first explored and settled by the Spanish until today, Arizona has remained sparsely populated, her topography and mineral riches both helping and hindering settlement.

During the 1500s, Spanish explorers rode from Mexico in quest of Christian converts and mineral wealth to rival Aztec and Inca treasure. In 1583, Antonio de Espejo’s expedition found copper and silver in the mountains near today’s Jerome. By 1598, Marcos de Farfán de Godos’ party returned from central Arizona. They didn’t find mineral riches but discovered the Verde River Valley’s “splendid pastures, fine plains, and excellent land for farming.” The Spanish never stayed to farm, ranch or mine.

During the 1500s, Spanish explorers rode from Mexico in quest of Christian converts and mineral wealth to rival Aztec and Inca treasure. In 1583, Antonio de Espejo’s expedition found copper and silver in the mountains near today’s Jerome. By 1598, Marcos de Farfán de Godos’ party returned from central Arizona. They didn’t find mineral riches but discovered the Verde River Valley’s “splendid pastures, fine plains, and excellent land for farming.” The Spanish never stayed to farm, ranch or mine.

What became Arizona was Mexican territory at the beginning of the fur trade. While Americans could live there, Mexican officials wouldn’t license them to trap, making trapping expeditions by Ewing Young, James Ohio Pattie and others to the Gila, Salt and Colorado rivers in the 1820s and 1830s illegal.

In 1846, war erupted between the U.S. and Mexico. The Army of the West commanded by Brigadier General Stephan Watts Kearny marched from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas with orders to occupy California. Eventually, Kearney and one hundred soldiers, guided by Kit Carson, followed the Gila River across today’s Arizona on a trail well-known to trappers.

In 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican war. This and the subsequent 1854 Gadsden Purchase prompted the U.S. government to launch expeditions by army officers to explore, map, and record the geography, geology, and natural history of the newly acquired Southwest.

Four expeditions were conducted by the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers in the 1850s to map remote parts of lands acquired from Mexico. The Sitgreaves Zuni and Colorado River Survey, Whipple Railroad Route Survey, Ives Colorado River Survey and Beale Wagon Road Survey helped open central Arizona to settlement during its territorial period.

Lorenzo Sitgreaves’ mission was to see if the Zuni, Little Colorado and Colorado rivers were navigable. Starting at the Zuni villages in September 1851, with Antoine Leroux as guide, the plan was modified and they headed west to intersect the Colorado River below the Grand Canyon. This would eventually become the Santa Fe Railroad route .

In 1853-1854, Amiel Weeks Whipple, guided by Antoine Leroux, commanded the Pacific Railroad Survey through northern Arizona along the 35th parallel. With him were Heinrich Balduin Möllhausen as artist-naturalist and Lieutenant Joseph Ives as his assistant. Collections and reports from the survey provided the most complete description of the landscape, plants, and wildlife that had been gathered in northern Arizona.

In 1853-1854, Amiel Weeks Whipple, guided by Antoine Leroux, commanded the Pacific Railroad Survey through northern Arizona along the 35th parallel. With him were Heinrich Balduin Möllhausen as artist-naturalist and Lieutenant Joseph Ives as his assistant. Collections and reports from the survey provided the most complete description of the landscape, plants, and wildlife that had been gathered in northern Arizona.

Edward Fitzgerald Beale was the catalyst behind Congress appropriating $30,000 in 1857 for camels for military transportation. He was appointed to survey a wagon road across the thirty-fifth parallel using camels to transport his equipment. The camels worked well but were lost in the shuffle of war preparations.

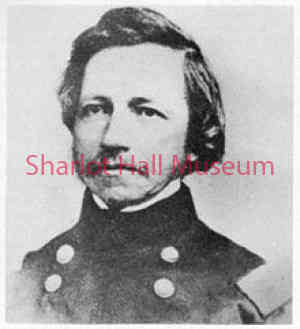

Joseph Christmas Ives accompanied Lieutenant Whipple on his railroad survey, assuring his next assignment, a hydrologic and geologic survey of the Colorado River, the largest river not surveyed by the army. Equipped with a steamboat, the “Explorer,” Ives spent part of 1857 and 1858 traveling 530 miles up the river to determine the head of navigation. He then returned to the Mohave Valley where he prepared a land expedition to survey the edge of the Grand Canyon and then to Fort Defiance.

The opening of the Central Mountain region by the Walker Party in 1863 was the final chapter in exploration. This, however, is another story.

This article is a preview of a presentation Mick will make at the Seventeenth Annual Western History Symposium that will be held at the Sharlot Hall Museum Education Center on November 7th. The Symposium is co-sponsored by the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International and is open to the public free of charge on a limited-admission basis. Face coverings are required. The presentations will also be streamed “live” on the website. For more details, call the Museum at (928) 277-2002.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at https://www.sharlot.org/articles/days-past-articles.l. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Research Center reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.