By Leo Banks

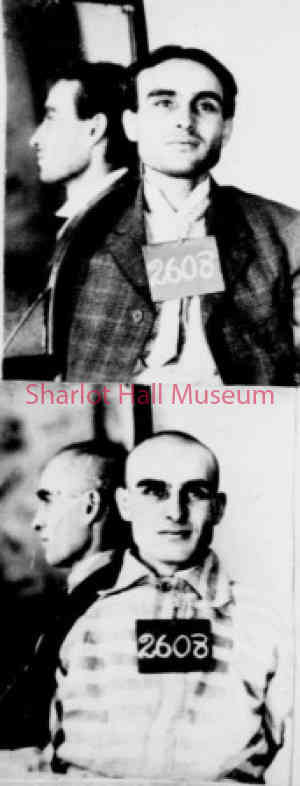

Perhaps the most cold-blooded conman early Arizona ever knew, Louis Eytinge suffered from tuberculosis, weighed 119 pounds and had two months to live. He should’ve died unknown, another bankrupt soul in a rugged land struggling to emerge from its frontier past. Yet upon entering Yuma Territorial Prison in 1907, prisoner No. 2608 made a remarkable comeback. By 1922, he was celebrated nationwide.

Eytinge earned his prison stay by murdering his boarding house roommate John Leicht. The two had gone on a picnic in the desert outside Phoenix. A week later, searchers discovered Leicht’s decomposing body, along with chloral hydrate, chloroform and an “E”-embroidered hanky. Louis laced Leicht’s whiskey with chloral hydrate (knockout drops) and held a chlorofoam-soaked hanky over his face, then rifled his pockets and left him to die.

Eytinge earned his prison stay by murdering his boarding house roommate John Leicht. The two had gone on a picnic in the desert outside Phoenix. A week later, searchers discovered Leicht’s decomposing body, along with chloral hydrate, chloroform and an “E”-embroidered hanky. Louis laced Leicht’s whiskey with chloral hydrate (knockout drops) and held a chlorofoam-soaked hanky over his face, then rifled his pockets and left him to die.

On April 8, 1907, detectives corralled Eytinge in San Francisco, where he’d been “spending money in the tenderloin like a Nevada mining millionaire,” the San Francisco Call reported. “You got me too soon,” Eytinge said. “If you had given me until next Saturday, I would have floated about $2,000 of phony paychecks and cleaned up for a trip to Honolulu.”

Eytinge denied committing the murder, saying Leicht was suicidal and had likely killed himself. He explained that he possessed the victim’s money and jewelry after winning them in a gambling game. The trial mesmerized Arizona Territory. Eytinge fed the sensation with provocative statements, including calling the prosecutor a “human vampire.”

The Tucson Citizen described the accused as probably the most peculiar man that ever faced a jury. “There is no question,” the paper said, “but that he is afflicted with moral insanity and does not realize his own depravity.”

The jury didn’t buy Eytinge’s insanity claim, convicting him, on June 4, of first-degree murder.

Louis was born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1878, to actors Harry Eytinge and Ida Seebohm. Historian James Kearney suggested Louis chose crime after watching his father play a British forger in a play. Reform school did nothing to change the teenager. He briefly attended college at Notre Dame and joined the Navy but got thrown out for stealing. After a stay at the Dayton Hospital for the Insane, he returned to crime.

In almost 16 years of confinement in Arizona – in Yuma and then Florence, where the prison moved in 1909 – Eytinge carried on a thriving advertising business, earning some $5000 a year. He won awards for his direct mail sales letters, one of which, according to the Republican, “is reputed to have broken all world records as to replies and results.” From his prison office, he edited a direct-mail magazine and helped the government with a Liberty Bond drive during World War I. In 1922, Universal Pictures released a movie, Man Under Cover, based on a story Eytinge wrote.

In almost 16 years of confinement in Arizona – in Yuma and then Florence, where the prison moved in 1909 – Eytinge carried on a thriving advertising business, earning some $5000 a year. He won awards for his direct mail sales letters, one of which, according to the Republican, “is reputed to have broken all world records as to replies and results.” From his prison office, he edited a direct-mail magazine and helped the government with a Liberty Bond drive during World War I. In 1922, Universal Pictures released a movie, Man Under Cover, based on a story Eytinge wrote.

Along with other influential progressives, Arizona Governor George W. P. Hunt fell hard for Eytinge. He solicited the inmate’s advice about legislation and the two became friends.

Eytinge’s gift was bringing people to his side, especially women. With equal ease, the handsome conman with “splendid dark eyes” and a dagger tattoo on his left forearm could talk a rooster out of crowing and a woman out of her assets, and much else. Newspapers described him as “one of the most romantic figures the underworld has ever produced.” At his parole in December 1922, a band played at the Florence prison as inmates gathered to see him off, calling out, “Goodbye, Papa Eytinge!” The 45-year-old had tears in his eyes.

The New York Times covered his release on its front page, and of course, there was a woman involved. Pauline Diver worked for a Manhattan publisher and had helped him, as one newspaper said, “come up from perversion.” But by 1927, he had cleaned out Diver’s bank account and split. His last romance, with a nurse in Los Angeles County, earned him a conviction for grand theft in 1933 and prison time.

His trail went as cold as his kiss until news out of Pennsylvania reported the 60 year old had died there from heart failure, on December 17, 1938. This wicked and brilliant criminal was reportedly buried in an unmarked grave.

Note: This article was published in the July issue of True West magazine. Visit the magazine’s website at TWMag.com

Leo Banks is a free-lance writer from Tucson. This article is a preview of a presentation he will make at the Fifteenth Annual Western History Symposium that will be held at the Prescott Centennial Center on August 4th. The Symposium is co-sponsored by the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral and is open to the public free of charge. For more details, call the Museum at 445-3122 or visit the sponsors’ websites at www.sharlothallmuseum.org and www.prescottcorral.org.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at https://sharlothallmuseum.org/articles/days-past-articles.l. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.