By Heidi Osselaer

The circumstances surrounding Arizona’s deadliest gunfight were so improbable, most people believed vengeance was the only logical explanation. After all, why would a federal posse travel all night on horseback over rugged terrain with a winter storm approaching to arrest men for non-violent crimes?

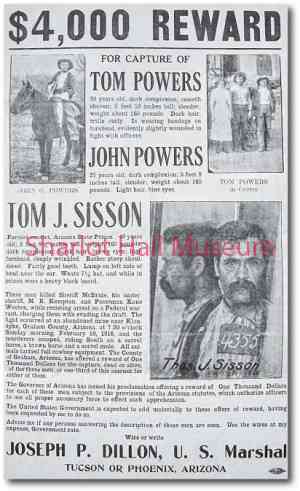

The bungled arrest attempt resulted in the deaths of four men—three Graham County lawmen and the owner of a mining claim in the Galiuro Mountains. Although evidence suggested the officers initiated the gunfight when they surrounded the cabin at dawn on Sunday, February 10, 1918, the surviving occupants of the cabin were found guilty of premeditated murder and sentenced to life in prison.

For years theories attempting to explain the gunfight proliferated in Graham County. Proponents of the slain sheriff and his two deputies said gold miners Jeff Power, his sons Tom and John, and hired hand Tom Sisson bristled at the rule of law, so they ambushed and viciously murdered the lawmen. Power sympathizers insisted the accused were asleep when the posse appeared at their doorstep determined to kill them--but could not agree what caused the blood lust. Some argued the sheriff wanted their gold mine, while others said a deputy and Tom Power were rivals for a woman. Yet another faction suggested tempers flared over grazing rights.

For years theories attempting to explain the gunfight proliferated in Graham County. Proponents of the slain sheriff and his two deputies said gold miners Jeff Power, his sons Tom and John, and hired hand Tom Sisson bristled at the rule of law, so they ambushed and viciously murdered the lawmen. Power sympathizers insisted the accused were asleep when the posse appeared at their doorstep determined to kill them--but could not agree what caused the blood lust. Some argued the sheriff wanted their gold mine, while others said a deputy and Tom Power were rivals for a woman. Yet another faction suggested tempers flared over grazing rights.

The only agreement was that the arrest attempt was pure lunacy.

Early histories suggested that a personal vendetta ignited the affair. But there were so many explanations for the bad blood, it was hard to figure out which was correct, leaving more questions than answers. With a careful review of public records, it quickly became clear this gun battle was not the result of an Old West grudge match, but rather a product of wartime hysteria.

When federal authorities instituted the first large-scale draft in American history in 1917, the public was slow to warm to the idea. Newspaper articles were filled with the horrors of trench warfare in Europe—including incapacitating mustard gas attacks and mass slaughter. Government officials knew it would be an uphill battle to convince young men to register to fight in a foreign war, so propaganda was liberally employed to win them over.

In the process, all sense of proportion was lost. Although failing to register was only a federal misdemeanor, draft evaders were condemned as enemies of the state and many newspaper editors demanded they be executed. Anyone who failed to buy a war bond or join the American Red Cross risked a beating by neighborhood thugs. Congress passed the Espionage Act which effectively outlawed free speech, requiring censors to expunge antiwar comments from newspapers and encouraging individuals to report anyone who spoke against the war.

Despite the federal crusade, an estimated three million men failed to register for the draft during World War I. Among them were Tom and John Power. Their father, Jeff Power, was no friend of the conflict either, telling a shopkeeper in the Gila Valley, “This is your war. . . we don’t want nothing to do with your war.”

After the shootout, testimony from a convicted perjurer was used to prove premeditation. In peacetime no reputable attorney would place such an unreliable witness on the stand, but, as George Bernard Shaw said, United States courts during the war “were stark, staring, raving mad.” Even the prosecutor who put them away for life later confided, “the Power brothers could not have received a fair hearing anywhere in the country.”

The Power brothers and Sisson languished in prison for decades, not even allowed a parole hearing until 1953 because sentiment was so strong against them. Tom Sisson died in 1957 at age 87, and many questioned why the Power brothers, by then in their sixties, remained behind bars. Reporters interviewing Graham County residents revived the many feud stories that had been circulating for decades, and suddenly the men once dubbed the “monsters of 1918” were recast by the press as victims of corrupt lawmen. With overwhelming public support for their release, a parole board freed them in 1960, and almost a decade later, when attitudes towards draft evaders had softened during the Vietnam War, Arizona’s governor granted them a full pardon.

Independent historian Heidi J. Osselaer is the author of “Arizona’s Deadliest Gunfight: Draft Resistance and Tragedy at the Power Cabin, 1918”, University of Oklahoma Press. Join Dr. Osselaer for a free lecture on the Deadliest Gunfight on Saturday, July 21 at 2 p.m. in the West Gallery of Sharlot Hall Museum’s Lawler Exhibit Center.

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at https://sharlothallmuseum.org/articles/days-past-articles.l. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.