By Bob Harner

While Buffalo Bill Cody’s wild west show remains famous, in his time Cody faced competing western showmen. One largely forgotten today is Arizona Charlie Meadows.

Born Abraham Henson Meadows, March 10, 1860 in Visalia, California, his father (a Confederate sympathizer) changed his name to Charles when Lincoln was elected. In 1877, the family moved north of Payson to Diamond Valley. In 1882, Charlie (then 22) was asked to guide an army detachment to the Mogollon Rim. In his absence, Apaches attacked his homestead, killing his father and wounding two of his brothers, one of whom later died.

Born Abraham Henson Meadows, March 10, 1860 in Visalia, California, his father (a Confederate sympathizer) changed his name to Charles when Lincoln was elected. In 1877, the family moved north of Payson to Diamond Valley. In 1882, Charlie (then 22) was asked to guide an army detachment to the Mogollon Rim. In his absence, Apaches attacked his homestead, killing his father and wounding two of his brothers, one of whom later died.

An experienced cattle rancher, Charlie began competing in roping competitions, riding his horse Snowstorm to win a July 4th Prescott event in 1886 and getting his first taste of show business performing roping demonstrations at carnivals and visiting side shows. In the April 1888 edition of Prescott’s Hoof n’ Horn, Charlie issued this challenge: “Charlie Meadows of Payson . . . challenges any man in the world to an all-round cowboy contest for $500 or $1000 a side . . . expert cowpunchers make a note of this.” A few months later, at the Phoenix Territorial Fair, he beat well-known Tom Horn for the title “King of the Cowboys” and set a record for steer tying (59 seconds). At the 1889 fair, Horn beat Charlie for the title.

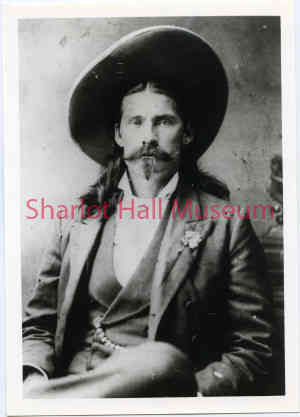

By 1890, Cody’s show was touring Europe, while Charlie’s cattle business was failing. In Australia, the Wirth Brothers’ Circus wanted its own wild west show, hiring experienced showman Captain “Happy Jack” Sutton to recruit performers. Having seen Charlie perform, Sutton hired him. Sailing for New Zealand, the troupe consisted of 15 cowboys, 12 Indians, two Mexicans and three female performers (one of whom, Sutton’s wife, passed away during the voyage). Onboard, Charlie cultivated long hair and a beard and mustache, imitating his admitted idol, Buffalo Bill.

In New Zealand, the Wirth Brothers’ show was a hit, drawing thousands for staged Indian attacks, a fake lynching and cowboy skill demonstrations. Charlie emerged as the natural leader of the troupe. In his autobiography, George Wirth described Charlie as “a very tall, fine-looking fellow with plenty of assurance and of cultivated manner.”

In New Zealand, the Wirth Brothers’ show was a hit, drawing thousands for staged Indian attacks, a fake lynching and cowboy skill demonstrations. Charlie emerged as the natural leader of the troupe. In his autobiography, George Wirth described Charlie as “a very tall, fine-looking fellow with plenty of assurance and of cultivated manner.”

Unhappy with their pay, Charlie led most of the cowboys to desert the Wirths and form their own troupe called Wild America. After New Zealand, they continued to Australia, where they were even more popular. A Melbourne newspaper reported about Charlie: “Never was a finer picture of American Manhood presented.”

Offered generous salaries, Charlie’s group signed with Harmston’s Great American and Continental Cirque for their Australian tour. With Harmston was sharpshooter “Doc” Carver, who taught Charlie the showman’s trick of using bird shot in his shells, making it easier to shoot objects in the air while letting spectators assume normal bullets were used. Charlie now became a sharpshooter.

While touring, Charlie took up with a young Australian girl, Marion Mae Murray, a trick rider with the circus. On tour in Java, the wild west performers left Harmston to join Frank Fillis’ Great Circus and Menagerie. Marion remained with Charlie as they toured Singapore and Penang (where they left Fillis and rejoined Harmston), followed by Delhi, Calcutta, Burma, Singapore again, the Philippines, Hong Kong and Shanghai. Between stops, Charlie and Marion married on shipboard. Charlie switched employers again and toured Japan.

Meanwhile, Buffalo Bill was planning a final European tour. Having been told about Charlie, he offered him a job. Eager to work with his idol, Charlie (with a now-pregnant Marion), sailed for Vancouver. Marion (ready to raise a family) informed Charlie that if he went to Europe, she would leave him.

Charlie joined Buffalo Bill in London on August 10, 1892.

(Next: Charlie back in Arizona)

“Days Past” is a collaborative project of the Sharlot Hall Museum and the Prescott Corral of Westerners International (www.prescottcorral.org). This and other Days Past articles are also available at https://www.sharlot.org/articles/days-past-articles.l. The public is encouraged to submit proposed articles and inquiries to dayspast@sharlothallmuseum.org. Please contact SHM Library & Archives reference desk at 928-445-3122 Ext. 2, or via email at archivesrequest@sharlothallmuseum.org for information or assistance with photo requests.