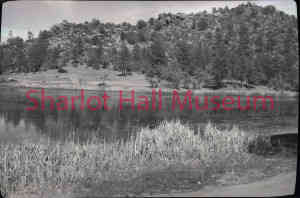

Granite Basin Lake Area

details

Mildred Tucker Unknown 1250.0394.0007.jpg LA - 394 B&W 1250-0394-0007 1250.0394.0007 Original Negative <2x3 Historic Photographs 1952 Reproduction requires permission. Digital images property of SHM Library & ArchivesDescription

Granite Basin Lake Area, Yavapai County, Arizona.

Purchase

To purchase this image please click on the NOTIFY US button and we will contact you with details

The process for online purchase of usage rights to this digital image is under development. To order this image, CLICK HERE to send an email request for details. Refer to the ‘Usage Terms & Conditions’ page for specific information. A signed “Permission for Use” contract must be completed and returned. Written permission from Sharlot Hall Museum is required to publish, display, or reproduce in any form whatsoever, including all types of electronic media including, but not limited to online sources, websites, Facebook Twitter, or eBooks. Digital files of images, text, sound or audio/visual recordings, or moving images remain the property of Sharlot Hall Museum, and may not be copied, modified, redistributed, resold nor deposited with another institution. Sharlot Hall Museum reserves the right to refuse reproduction of any of its materials, and to impose such conditions as it may deem appropriate. For certain scenarios, the price for personal usage of the digital content is minimal; CLICK HERE to download the specific form for personal usage. For additional information, contact the Museum Library & Archives at 928-445-3122 ext. 14 or email: orderdesk@sharlot.org.