Bartlett Dam

details

Unknown Unknown 1025.0136.0011.jpg DAM-136 B&W 1025-0136-0011 1025.0136.0011 Print 8x10 Historic Photographs c. 1939 Reproduction requires permission. Digital images property of SHM Library & ArchivesDescription

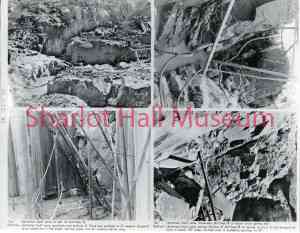

Photos of Bartlett Dam, located on the Verde River, located fifty (50) kilometers northwest of Phoenix, Arizona.

Top left: Upstream falut zone to left of buttress 8.

Top right: Upstream fault zone traversing buttress 9 at about arch spring line.

Bottom left: Upstream fault zone upstream end buttress 5. Zone has pinched to 3"; several diagonal grout pipes are in the zone. Vertical pipes are for holding forms only.

Bottom right: Upstream fault zone across footing of buttress 8 at spring of arch. In the foreground zone is about 30" wide, futher over it suddenly pinches to 8".

Source: Bureau of Reclamation, Bartlett Dam: Foundation Rocks and Engineering Treatment § (1939).

Purchase

To purchase this image please click on the NOTIFY US button and we will contact you with details

The process for online purchase of usage rights to this digital image is under development. To order this image, CLICK HERE to send an email request for details. Refer to the ‘Usage Terms & Conditions’ page for specific information. A signed “Permission for Use” contract must be completed and returned. Written permission from Sharlot Hall Museum is required to publish, display, or reproduce in any form whatsoever, including all types of electronic media including, but not limited to online sources, websites, Facebook Twitter, or eBooks. Digital files of images, text, sound or audio/visual recordings, or moving images remain the property of Sharlot Hall Museum, and may not be copied, modified, redistributed, resold nor deposited with another institution. Sharlot Hall Museum reserves the right to refuse reproduction of any of its materials, and to impose such conditions as it may deem appropriate. For certain scenarios, the price for personal usage of the digital content is minimal; CLICK HERE to download the specific form for personal usage. For additional information, contact the Museum Library & Archives at 928-445-3122 ext. 14 or email: orderdesk@sharlot.org.