Johnson Canyon Railroad Trestle Bridge

details

Unknown Continent Steroscopic Company rr0191p.jpg RR-0191 B&W 1070-0191-0000 rr0191p Print 5x7 Historic Photographs 1915 Reproduction requires permission. Digital images property of SHM Library & ArchivesDescription

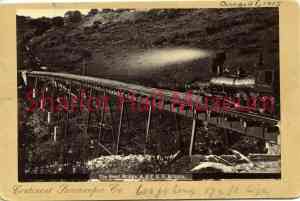

Photo shows a train going full steam on the Johnson Canyon railroad trestle bridge (G-389), 600 feet long and 172 feet high, built in 1881-1882 as part of the Santa Fe Railroad (formerly known as the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad). This portion of the railroad is located near Williams, Arizona.

Johnson Canyon is located between Williams and Ash Fork, Arizona on the Santa Fe Railroad. This section of the railroad turned out to be the most difficult stretch on the Santa Fe railway from Kansas City to Los Angeles due to the hard basalt rock, which required blasting to create the Johnson Canyon railroad tunnel. Project work on the 328-foot tunnel began in April of 1881 and continued until the following April. This tunnel was the only one west of Albuquerque, New Mexico on the Santa Fe rail line.

Once the tunnel construction was complete, work began on the two trestle bridges to span Johnson Canyon–it was the only segment on the railroad in Arizona that required two. According to Marshall Trimble in his blog “Johnson Canyon Was Blessed or Cursed With a Stretch of Extreme Hard Basalt Rock That Required Blasting a Way Through and Building a Tunnel,” True West Blog, 2020, James T. Simms was contracted to complete the Johnson Canyon segment with the two trestle bridges. The Simms construction camp housed between 1,500-3000 workers, more than the town of Williams itself. The workers left Simms a ghost town when they broke camp upon the segment’s completion in 1882. By August 1883 the railroad reached Needles, Arizona.The latter part of the track was finished in June by a Mr. Keepers, the same man who built the Date Creek Bridge of the Union & Pacific Railroad (UPRR).

The 1,000-foot climb required two helper engines to push eastbound freight trains up the canyon. Down wasn’t much easier, and the hard brakes left many trains wrecked at the bottom of the canyon.

To protect the tunnel from saboteurs, a machine gun nest protected the tunnel and trestle during World War II. In the late 1940s they replaced the trestles with a landfill. By 1960 Santa Fe abandoned Johnson all together, for the fast and flatter line across the prairie.

Reference:

Trimble, Marshall, (January 21, 2020). “Johnson Canyon Was Blessed or Cursed With a Stretch of Extreme Hard Basalt Rock That Required Blasting a Way Through and Building a Tunnel,” True West Blog, 2020.

Johnson Canyon is located between Williams and Ash Fork, Arizona on the Santa Fe Railroad (formerly known as the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad). This section of the railroad turned out to be the most difficult stretch on the Santa Fe railway from Kansas City to Los Angeles due to the hard basalt rock, which required blasting to create the Johnson Canyon railroad tunnel. Project work on the 328-foot tunnel began in April of 1881 and continued until the following April. This tunnel was the only one west of Albuquerque, New Mexico on the Santa Fe rail line.

Once the tunnel construction was complete, work began on the two trestle bridges to span Johnson Canyon–it was the only segment on the railroad in Arizona that required two. According to Marshall Trimble in his blog “Johnson Canyon Was Blessed or Cursed With a Stretch of Extreme Hard Basalt Rock That Required Blasting a Way Through and Building a Tunnel,” True West Blog, 2020, James T. Simms was contracted to complete the Johnson Canyon segment with the two trestle bridges. The Simms construction camp housed between 1,500-3000 workers, more than the town of Williams itself. The workers left Simms a ghost town when they broke camp upon the segment’s completion in 1882. By August 1883 the railroad reached Needles, Arizona.

The 1,000-foot climb required two helper engines to push eastbound freight trains up the canyon. Down wasn’t much easier, and the hard brakes left many trains wrecked at the bottom of the canyon.

To protect the tunnel from saboteurs, a machine gun nest protected the tunnel and trestle during World War II. In the late 1940s they replaced the trestles with a landfill. By 1960 Santa Fe abandoned Johnson all together, for the fast and flatter line across the prairie.

Reference:

Trimble, Marshall, (January 21, 2020). “Johnson Canyon Was Blessed or Cursed With a Stretch of Extreme Hard Basalt Rock That Required Blasting a Way Through and Building a Tunnel,” True West Blog, 2020.

Purchase

To purchase this image please click on the NOTIFY US button and we will contact you with details

The process for online purchase of usage rights to this digital image is under development. To order this image, CLICK HERE to send an email request for details. Refer to the ‘Usage Terms & Conditions’ page for specific information. A signed “Permission for Use” contract must be completed and returned. Written permission from Sharlot Hall Museum is required to publish, display, or reproduce in any form whatsoever, including all types of electronic media including, but not limited to online sources, websites, Facebook Twitter, or eBooks. Digital files of images, text, sound or audio/visual recordings, or moving images remain the property of Sharlot Hall Museum, and may not be copied, modified, redistributed, resold nor deposited with another institution. Sharlot Hall Museum reserves the right to refuse reproduction of any of its materials, and to impose such conditions as it may deem appropriate. For certain scenarios, the price for personal usage of the digital content is minimal; CLICK HERE to download the specific form for personal usage. For additional information, contact the Museum Library & Archives at 928-445-3122 ext. 14 or email: orderdesk@sharlot.org.