Granite Reef Dam

details

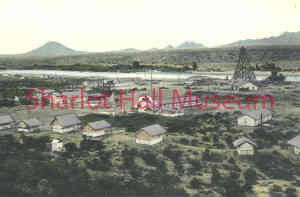

Unknown Unknown dam105pb.jpg DAM-105 Hand-Tinted Color 1025-0105-0002 dam105pb Postcard 3x5 Historic Photographs c. 1900 Reproduction requires permission. Digital images property of SHM Library & ArchivesDescription

Picture shows the construction of the Head Gate for the Granite Reef Dam. The Granite Reef Diversion Dam is a concrete diversion dam located 22 miles (35 km) Northeast of Phoenix, Arizona, on the Salt River. The dam is 1,000 feet (300 m) long, 29 feet (8.8 m) high and was built between 1906 and 1908 for the Salt River Project, who currently operates the dam. It replaced the older Arizona Dam which was washed out in a flood in 1905. Coordinates: 33°30′58″N 111°41′28″W. The dam diverts most all water in the Salt River into the Arizona and South Canals serving metropolitan Phoenix with irrigation and drinking water. The Salt River below Granite Reef is usually dry except following consistent and heavy upstream precipitation. When upstream lakes are full, minor and moderate releases are accomplished via floodgates at either end of the dam. The dam is designed to be overtopped by major releases, which can occur every 10 to 40 years. The dam is owned by the United States Bureau of Reclamation and operated by the Salt River Project.

Purchase

To purchase this image please click on the NOTIFY US button and we will contact you with details

The process for online purchase of usage rights to this digital image is under development. To order this image, CLICK HERE to send an email request for details. Refer to the ‘Usage Terms & Conditions’ page for specific information. A signed “Permission for Use” contract must be completed and returned. Written permission from Sharlot Hall Museum is required to publish, display, or reproduce in any form whatsoever, including all types of electronic media including, but not limited to online sources, websites, Facebook Twitter, or eBooks. Digital files of images, text, sound or audio/visual recordings, or moving images remain the property of Sharlot Hall Museum, and may not be copied, modified, redistributed, resold nor deposited with another institution. Sharlot Hall Museum reserves the right to refuse reproduction of any of its materials, and to impose such conditions as it may deem appropriate. For certain scenarios, the price for personal usage of the digital content is minimal; CLICK HERE to download the specific form for personal usage. For additional information, contact the Museum Library & Archives at 928-445-3122 ext. 14 or email: orderdesk@sharlot.org.